Emotion, "inpletion," and devotion: part 1

What evokes calm, deep feeling rather than agitated emotions?

Three recent posts—Inner experience: a unique value of written stories and “The privilege of writing inner experiences” part 1 and part 2—looked at different aspects of expressing a character’s inner experience in written fiction, including a comparison with acting, the other form that asks artists to get into the hearts and minds of fictional characters. Those posts also suggested that holding oneself in an emotional space for extended periods of time places unique demands upon writers themselves.

From what I’ve observed from other authors’ accounts of their process (often shared in “Author’s Notes”), it seems that those demands can and do take their toll on authors’ well-being and even mental health. Put another way, although their craft sometimes serves writers as therapy,1 it also sometimes seems to put them into therapy.

It seems, too, that this is just an accepted price to pay for the creation of impactful stories, because fiction, so the dogma goes, is all about emotion. But I want to challenge that dogma because there are also calm, deep feelings that just don’t seem to fall on the same emotional spectrum as anger, depression, excitement, disgust, and so forth.2

What is the nature of those deeper feelings? Do they have a place in the craft of fiction? And how do they help writers and artists in general avoid the emotional exhaustion (even trauma) that is so often assumed to be an integral and unavoidable part of the creative process? Those are the questions I’ll explore in this and the post that follows, because the answers offer a different approach to writing fiction that I think is more appropriate, too, for the expression of spiritual, devotional, and mystical realism.

Is the purpose of story merely to create emotion?

Every book and course I’ve looked at about the craft of fiction stresses emotion. The drum beats again and again: emotion, emotion, emotion. I can understand why: people do read fiction (and watch movies) to feel something and to share in the innermost experiences of the characters. For consumers, sharing that intimate inner experience is the special purview of written stories. And emotion is a pretty sure-fire way to keeps readers engaged and invested in a story.

But consider two other factors.

First, is emotion the sole compelling characteristic of stories? Is emotion the only reason why people read? It’s one reason, yes, but I think a more fundamental reason why people enjoy stories is because they get to experience a different life, including and perhaps especially a life well outside our present-day reality in time, space, and setting. And the core of this escapism, if you will, is less about getting outside the limitations of one’s everyday reality than it is about getting outside oneself. That is, fiction allows you to take a liberating break from the dominance of your ego, from the pains of self-involvement, and from the tyranny of the “I’m-the-center-of-the-universe” miasma.

To share in the inner experience of another is to expand one’s sense of self, one’s sympathies, and one’s consciousness, all of which are spiritually fulfilling regardless of whether you consider yourself “spiritual.” As a “non-believing acquaintance” said to authors Ernest Kurtz and Katherine Ketchem with regards to the section called “Prayer” in their book, Experiencing Spirituality: Finding Meaning through Storytelling: “It’s nice to have moments when I’m not thinking about me.”

Spiritual expansion, in short, is more fulfilling than a mere emotional ride, for it’s in that expansion that you find a connection with something larger than yourself. You connect with meaning. You connect with God. And this is something that mystical realism in fiction can inspire in readers.

Second, this whole assumption about emotion in fiction is based on an equivocation or perhaps a common blindness. By and large, we use “emotions” and “feelings” interchangeably. But the calm, deep feeling that we’re talking about here, which is also impersonal even though experienced individually, is not quite the same thing as personal, self-involved emotion.

Recall a time when your favorite sports team—one with whom you identify personally—won or lost a big game, and the emotions of excitement or dejection that you experienced then. Now take a moment to recall an experience of wonder, such as gazing at a scene of stunning natural beauty, when you pretty much forgot about yourself.

Then ask: are both of these really just emotional experiences? How much in common do the two types of experience really have?

Do the same exercise with emotions like anger, sadness, fear, disgust, and sensual pleasure, comparing them to feelings like calmness, peace, beauty, light, wisdom, and freedom.

Something tells us that these two lists are not quite the same sort of thing.

Singing in the Corycian Cave (Delphi, Greece)

Let me offer an example of why I say that these experiences are distinct.

In April 2023 my teenage son and I enjoyed touring parts of Greece with a number of friends. One day we visited the Corycian Cave in Parnassus National Park near Delphi, a site that’s been considered sacred for six thousand years.

The cave’s main chamber, measuring approximately 90x60 meters in breadth and 50 meters in height, provides similar acoustics to a cathedral. When presented with the lovely echo of a space like this (which includes tile-lined bathrooms at rest areas), I enjoy singing a piece called Psalm of David, which is Psalm 121 set to a melody by J. Donald Walters for his Christ Lives! oratorio.

(Here’s recording of Psalm of David that I performed in Grass Valley, CA, April 2006, as part of the full oratorio.)

Most people in my group knew the song, so I didn’t have any qualms about inflicting it upon them singing it. When I began, people were milling about in different parts of the cave with our Greek guides, chatting about its history or the many other chambers farther in. Within a short time, though, and especially after I sang two more songs (with which others joined in), the chatter stopped and people, including our guides, became quite still, just absorbing the final reverberations that flowed throughout the cave.

Here’s a short video (34s) that captured the end of the last song (a piece called Cloisters, also composed by J. Donald Walters):

So, what was it about this singing that brought people to a place of stillness? Even our guides commented on how deeply it moved them, which is to say, moved them to stillness. Clearly, whatever’s happening is different from music or singing that arouses and excites people, and the difference is whether the feelings involved are agitated or calm.

Agitated feelings vs. calm feelings

Emotions are agitated feelings that drive us to action and activity. Agitated feelings draw us outward into the senses, whether it be shouting because we’re angry or shouting because we’re excited.

This outward direction is even inherent the etymology of the word “emotion,” which comes from the Latin verb emovere, "to move out, remove, agitate," which is itself a compound of e/ex- “out, out from” plus movere “to move”.3 The very word suggests a spinning out away from one’s center.

Calm feelings like peace and wonder, on the other hand, are not so much aspects of emotion as they are of consciousness. Calm feelings draw us inward, away from the senses and toward a stillness wherein we can truly savor the experience in our souls. Think about it: do you want to jump up and down and cheer when directly experiencing a vibrant sunset, a majestic waterfall, or, as many people did recently, a total solar eclipse?4 No—you naturally stop and absorb the awe of the moment.

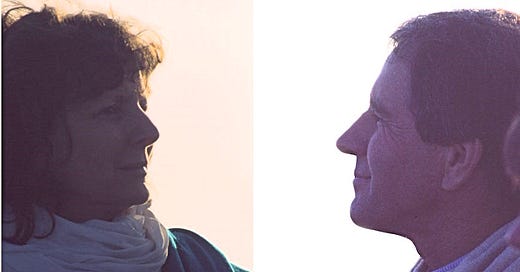

In the above photos, look at the countenances of two of my fellow pilgrims as we watched the sunrise on the high Himalaya (as related in a previous post). Their feelings are clearly deep, not agitated, and those feeling are drawing them not to outward movement but again to stillness and silence, into the center of their beings.

So, what do we call this counterbalance to emotion?

Unfortunately, although we have a single word for agitated feeling—emotion—from which we also derive other convenient forms like emotional, emotionally, and emotionalism, we don’t have a simple term for calm feeling that we can use in the same way.5

In fact, when we think of opposites to emotion we tend to think along the lines of thesaurus antonyms: coldness, indifference, apathy, insensitivity, and stoicism, all of which imply the absence of feeling. That’s definitely not what we’re looking for, because there’s certainly feeling involved. It’s just not agitated.

Because of the equivocation of “emotion” and “feeling” that I mentioned earlier, I think we just assume that calm, inwardly focusing feelings are just another kind of emotion. Why, then, would we need a specific word at all? What’s more, those deeper feelings are not something that most people seem to experience very often. And if they do, they don’t stay there for very long, given the general levels of anxiety and restlessness and the emotional turmoil that dominates many people’s lives.

It’s like those feelings occupy but a singular, dimensionless point of rest at the very center of the otherwise turbulent emotional spectrum, a point that you just don’t fall into by accident. You rather have to seek it out deliberately through practices like centering prayer, contemplation, meditation, and similar methods that specifically withdraw both from outward activity and from the senses. But still, we don’t have a specific word for this that we can use like we use “emotion.”

Well, then, we don’t we invent one?

Let’s start with the opposite of the Latin preposition e/ex- “out, out from,” which is in “in, into.” Swapping the prefixes produces an awkward word like inmotion, but that still implies movement based on movere. We really want a word that implies a coming into the cessation of movement. Not the cessation itself, for which we do have words like “stillness,” but rather a word for that which brings us to that center just as emotion draws us out.

We could use something based on the Latin tranquillitas, but words like “intranquilition” are rather cumbersome and “tranquilization” suggests a stillness induced by sedative drugs. Not what we’re looking for here.

How about working from the Latin root plere “to fill,” from which we get words like “complete” and “completion” (com/cum meaning “with”)? It’s also the root of implere “to fill up.” Complere and implere both suggest an inner fulfillment—a wholeness—rather than an outward dissipation.

So how about a word like impletion (rhyming with completion) but changing im to in to avoid the idea of implosion (which is derived from implere)?

That makes this word:

inpletion

which we can define as “drawing to inner fulfillment or wholeness,” an opposite to the “driving to outer movement” of emotion.

Because inpletion ends with “tion,” we can easily make equivalent derivatives as we do with emotion, such as inpletional, inpletionally, and inpletionalism. Thus, when I speak of an experience like that in A matter of the heart, I can call it an inpletional experience. We can speak of people and characters in stories as responding inpletionally to an event as distinct from reacting emotionally. And with the effect of music, like that which I sang in the Corycian Cave, we can speak of an inpletional rather than a merely emotional effect.

What do you think?

And do you know of any novels or other stories that evoke an inpletional effect? I’d love to know.

Here I want to acknowledge Kathryn Vercillo’s work on her Create Me Free Substack that explores the complex relationship between creativity and mental health.

And to be clear, the “feelings” we’re talking about here are not the sensual feelings of touch but the feelings we usually associate with emotions.

The “t” in motion comes from one of the other Latin principal parts of movere, which provide the stems needed to conjugate the verb in all its forms. Movere is the infinitive; the present stem is moveo, “I move”; the perfect stem is movi, “I moved”; and the past participle is motus (or motum), which means, simply “moved.” The past participle is a “verbal” because it and its derivatives can be used as adjectives and nouns, such as our noun, motion, which gets the “t” from motus. Many other English words derived from Latin pick up a “t” from the past participle.

I didn’t observe the total eclipse in 2024 but witnessed the event in February 1979 (Yakima, Washington) and again in August 2017 (Ontario, Oregon).

Devotion, as we’ll see in part 2, means calm feeling that are uplifted towards God, which adds another dimension.