Transition points in seeking God

Inspiring readers to take those steps toward God for which they’re ready

(If you like this post, selecting the ❤️ to bless the Algorithm Angels.)

In our exploration of what it means “to inspire people to seek God” through story, The nature of inspiration, part 1, described different flavors of inspiration: emotional, inpletional, confirmational, and motivational. The specific type that has the greatest impact is motivational inspiration because, to quote that previous post, it’s “the one that moves you to act and/or change how you think and how you live.” Instead of speaking of being inspire by something, as with the other forms, motivational inspiration, as the name implies, moves us to do something: to play golf, to travel, to volunteer, to pray, to seek God.

Such actions, however, are but the outward expression of a corresponding inner change, and that inner change what we’re particularly interested in with fiction that inspires readers to seek God in some way.

To dig even deeper into the matter, there are several distinct elements of this inner inspiration that leads to meaningful change:

Greater inner clarity about what one’s life is about or at least about what’s possible;

Greater awareness about how to go about living with that clarity, which is to say, the different choices that one would have to make; and,

Greater will (and courage) to embrace those new possibilities and make the choices that turn potentiality into actuality.

These elements also distinguish true inspiration from mere emotional excitation; to use the language of my previous posts, they are inpletional rather than emotional, inward rather than outward.

Fiction can certainly deliver all three of these elements—to “touch the heart” in terms of touching and inspiring the heart of one’s being. Stories can do so regardless of their specific content or how, exactly, the author seeks to inspire readers. As authors, that is, we illuminate some aspect of what we believe life is about by creating characters with certain wants and give them a toolset with which to pursue those wants. We then thwart fulfillment of those wants through any number of situations that force characters to make difficult choices and bear the consequences. It’s this combination of choices, consequences, and the character’s responses that reveal what we, as authors, consider valuable.

Readers, for their part, get to play-act these situations and choices, gaining a degree of life experience without having to suffer the consequences directly. (Nor do readers get to enjoy the fruits of victory as deeply as the characters would if they were real people.) That experience, though, empowers readers to make more conscious—and therefore more meaningful—choices in their own lives as they seek fulfillment.

Connecting motivational inspiration with directional spirituality

Here is where we can now connect motivational inspiration, which again is examined in The nature of inspiration part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4, with directional spirituality and seeking God, discussed in Everyone is seeking God but most don’t know it and Stories that are spiritualizing don’t look spiritual part 1 and part 2.

Each of the behavioral patterns that we’ve been discussing—self-comforter, self-server, self-sacrificer, and self-transcender—have specific views as to what constitutes this “fulfillment.” Readers naturally relate best to characters who seek a similar type of fulfillment as themselves; I would say, in fact, that the nature of this fulfillment is what defines the target audience for any given story. You make that choice as an author.

For example, if your goal as an author is merely to entertain, then you can write a story in which the protagonist finds the same kind of fulfillment as readers in that pattern are themselves seeking. Such stories would deliver comfirmational inspiration only.

If, on the other hand, your goal is to uplift readers—which means to inspire them to rise upwards, if even a little bit, in the direction of God/Satchidananda wherein lasting fulfillment alone is found—then you’ll want to deliver appropriate motivational inspiration. I stress “appropriate” because you don’t want to overshoot your readers by asking too much of them, just like you wouldn’t ask a student who is just learning long division to suddenly jump to non-Euclidian geometry. There are many intermediate steps that the student must complete first.

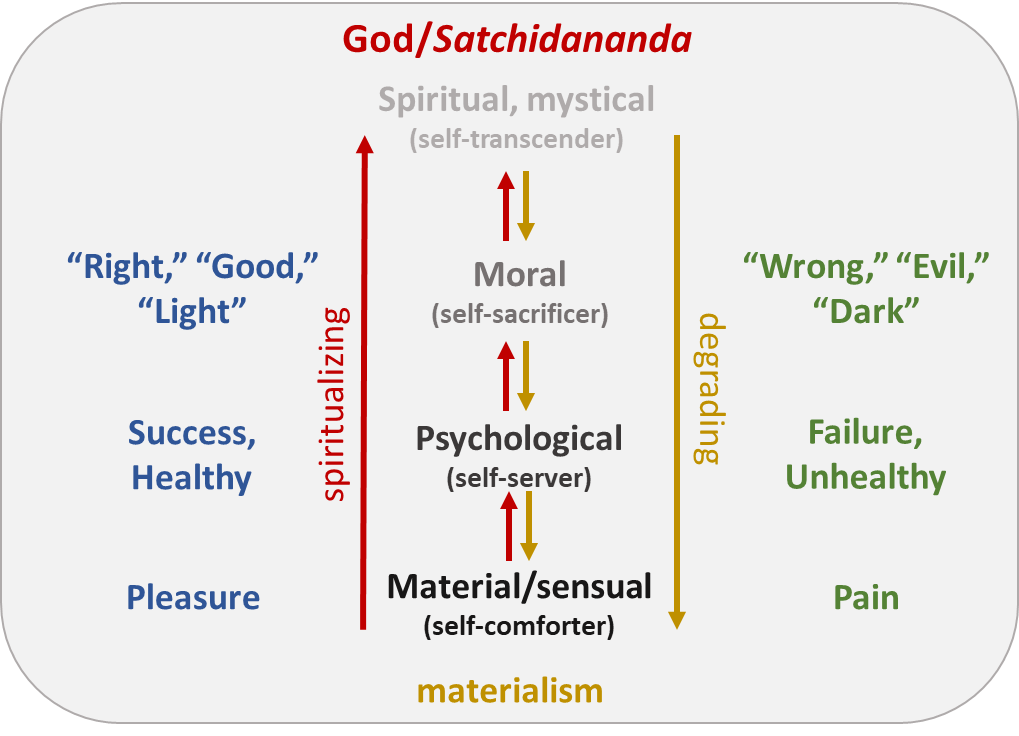

Within the framework of directional spirituality, any movement upwards toward the self-transcender pattern, as shown in the illustration below, is fundamentally spiritual because it's moving closer to God/Satchidananda. So, instead of asking readers in the self-server pattern, for example, to jump all the way to the worldview of a self-transcender, “appropriate” means inspiring them upwards first toward the higher levels of the self-server, and then from there, if it’s appropriate, perhaps to take their first steps into the pattern of the self-sacrificer. That’s really enough to aspire to within one story!

There is an exception to consider, though (besides a character making transitions over the course of a series): a story may involve a character who is fundamentally on a level, say, of the self-sacrificer, but falls or has fallen into a lower behavioral pattern. They have, in other words, already experienced a kind of tragic character arc, which might be depicted in the story itself or may just be part of the backstory. Such a character can first work to reclaim their inherent or default pattern and then rise a little higher. I think this is the core of “redemptive” stories in which a character may go all the way from self-comforter to self-transcender: they really weren’t truly a self-comforter to begin with. They had fallen only temporarily into that lower pattern, and they knew deep down that it’s not where they belonged.

In any case, I think that recognizing this overall directionality, driven by the fundamental motivation of seeking God, can give added depth—truth, even—to any kind of fictional character, just as it gives greater insight into the behavior of real human beings.

When writing to inspire readers, your protagonists can still begin their quests by seeking those fulfillments to which your target readers (those in your target behavioral pattern) can relate. But instead of simply putting obstacles in a character’s path to the expected fulfillment on that same level, have those obstacles compel them toward choices that bring a greater, and oftentimes unexpected, fulfillment. That is, have your protagonists run into those natural consequences and discontents mentioned in Everyone is seeking God but most don’t know it that compel them to make choices that are more aligned with a higher level. To repeat a passage from that post:

If we look at matters not statically but rather directionally, we can see that the natural consequences and discontents of the other three patterns of behavior inevitably lead people—compel them, really—toward the pattern of the self-transcender. For no matter how much they experience shallow and/or temporary gratifications, they must eventually admit that their thirst for lasting, inner joy remains unquenched.

It’s at the point when they decide to try a different approach that they take a step up to the next higher pattern—or even just entertain such taking that step—that they do grow closer to the true and lasting fulfillment of Satchidananda.

Such compulsion arises because for as much as one might hope that the fulfillments of the lower patterns are permanent, they cannot but be temporary because they’re not rooted in the Eternal Absolute. To quote C. S. Lewis again from Mere Christianity:

Most people, if they had really learned to look into their own hearts, would know that they do want, and want acutely, something that cannot be had in this world. There are all sorts of things in this world that offer to give it to you, but they never quite keep their promise. (Book III, Chapter 10, “Hope”)

Or, like Saint Augustine wrote at the beginning of his Confessions, “Thou hast made us for Thyself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it finds its rest in Thee.”

Repeated disappointment over those broken promises are the “natural consequences and discontents” that compel people to eventually adopt a different approach.

Depicting such upward-driving choices in fiction gives readers an awareness of new possibilities as well as the opportunity to play-act, rehearse, or simply visualize these transitions for themselves. Such, I believe, is the hallmark of motivational inspiration.

But let’s be clear about the directionality as it applies to the different patterns: to inspire any reader to rise upwards is to inspire them to draw closer to God, regardless of whether a story contains any explicit spiritual teachings or mentions of God, Spirit, etc.1 A self-comforter, for example, isn’t ready to think about seeking God directly, but they probably are motivated to seek greater energy and greater personal gain as a means to achieve the lasting comfort that has been denied them. That change lifts them toward God from their present reality because it lifts them toward the self-server pattern. Anything that inspires them in that direction is, for them, a fundamentally “spiritual” teaching, even if a story is thematically on the material or sensual level and even if the character is maniacally egotistical.2

The same is true for self-servers: they may not be ready to think about seeking God directly either, but they can be motivated to seek greater expansion of their sympathies and a greater willingness to share, which draws them toward God because it lifts them toward the self-sacrificer pattern. That’s what constitutes a “spiritual” teaching for them, even if a story deals only with psychological and occasionally moral themes.

For the self-sacrificer, a spiritual teaching is then whatever motivates them to rise to the behavioral pattern of the self-transcender where one begins to truly seek God directly. Such stories are thematically “moral” and perhaps dabble in the occasionally spiritual theme as well, just to prime the pump, so to speak.

And for the self-transcender, this is where spiritual themes related to seeking God may appear explicitly. Even so, self-transcenders may still not refer to “God”—they might instead be thinking Love, Peace, Wisdom, Beauty, Goodness, Truth any number of other transcendentals. It doesn’t really matter because their goal is that of the mystics in all traditions: conscious communion—and union—with greater, universal reality.3

Summing up and looking ahead

To sum up: inspiring readers to seek God means helping them:

Develop a greater inner clarity about a higher purpose of life than the pattern in which they presently live,

Visualize what living with that clarity could look like in the modern world (though readers may be able to infer such clarity from examples in a historical or future/fantasy world), and

Awakening the necessary will and courage to carry out the necessary choices in their own lives, the sense of “perhaps I can.” Courage—“having the heart” for the quest—is necessary because changes in the patterns of one’s life will challenge existing habits, routines, beliefs, and even relationships, all of which will put up a fight!

What we’ll do next in subsequent posts is delve into more detail about the transitions between the patterns and what it might look like for a story to inspire readers to make those transitions for themselves.

Until then, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

(If you like this post, selecting the ❤️ to bless the Algorithm Angels.)

Later posts will look more closely at the questions of spiritualizing effect vs. obvious spiritual content.

There are many levels of ego: the degenerate self-preoccupation of a self-comforter, including that of false humility (“I’m worthless”), is just as self-centered as the conceited braggart. The difference is one of energy: those who seek to build a business empire even at the expense of other people are most certainly operating on a higher level of energy than a person who merely panhandles for drugs.

This is why sincere Buddhists who seek transcendence in, say, Compassion or Dharma, are not at all atheists or materialists. They simply don’t relate to “God” as an Omnipotent Creator or divine being; they are nontheistic than atheistic.