The nature of inspiration, part 4

Forms of inspiration within story structure, Act 3-Climax and Conclusion

(If you like this post, bless the Algorithm Angels, the Digital Devas, or whatever you’d like to call them by selecting the “heart” icon ❤️ even if you’re not a subscriber. It helps!)

Part 2 introduced the use of inspiration in story structure as an extension of rhetoric and persuasive writing and Part 3 delved into Act 1—The Opening and Act 2—The Middle Cycle. In this concluding post, we’ll look at Act 3—Climax and Conclusion, though first it’s worth taking a pause to consider whether motivation inspiration is, in fact, what your audience is looking for.

Do your readers want motivational inspiration?

When we identified the elements of motivational inspiration in Part 1, the key difference between it and the other flavors of inspiration is change. Thus, if you’re looking to deliver some kind of experience of motivational inspiration in a story, remember that you’re asking a lot of your readers. Thus, it’s worth asking yourself whether it’s what your readers actually want.

The first element of motivational inspiration that Part 1 identified is a “greater inner clarity about what one’s life is about or at least about what’s possible.” That bit about “what’s possible” is something of a bridge between confirmational inspiration and motivational inspiration; it’s the first step into the inner change that leads to outer change in one’s life, but that might be all your audience is really wanting or really ready for.

To illustrate this edge, let me share an experience I had with an audience that was primarily looking for confirmation and the inspiration of new possibilities but not necessarily motivation to do anything different in their own lives.

In 2016, I was part of a team that helped organize a somewhat esoteric event called the Conference on Precession and Ancient Knowledge (CPAK, no relation to the Conservative Political Action Conference, CPAC). The conference is built around traditions found in a variety of ancient cultures—including classical Greece, Egypt, India, and I think some early South American cultures—that civilization ebbs and flows in repeating, cyclical patterns of four ages. These ages are called by various names: the Golden, Silver, Bronze, and Iron Ages or the Ages of Gods, Demi-Gods, Heros, and Common Man. In India the periods are called yugas, with the names Satya (Truth), Treta (Mind), Dwapara (Energy), and Kali (Dark). The conference basically explores various scientific and archaeological evidence (like Göbekli Tepe in Turkey) for the existence of high civilizations in the distant past as well as possible relationships between these cycles and the 24,000+ year precession of the equinoxes. Cosmic, “big picture” stuff, in other words.

Anyway, as we laid out the agenda, we needed to fill a half-hour slot in the late morning. I offered to give a talk on what these cycles of time might mean for us today. That is, the esoterica about ancient knowledge and such was well and good, but it left me asking, “So what? What bearing does it have on how we actually live?” That aspect—motivational inspiration—was generally absent from other content.

I enjoyed preparing and delivering my presentation, and it seemed to be received well enough despite the fact that I stood between attendees and their lunch. I fielded a few good questions, and I think a few people, at least, took away what I'd hoped to deliver. When we compiled all the session ratings a week or two later, though, my session ranked dead last. Not that the ratings were poor--like I said, the talk was received well enough. It's just that every other talk rated higher, some significantly so.

All of this told me that I hadn’t really understood the audience fully. The majority of attendees were there to be informed, perhaps "enlightened," but not inspired in the sense we're speaking of here. They simply weren’t interested in change. If there was any inspiration to be had, it was intellectual and primarily confirmational—of the head and not of the heart. Attendees reveled in hearing new theories, being privy to "new research," and having a chance to chat with the speakers, all of which were the inherent privileges of paying to attend, which engender the sense of pride or elitism that's found within any specialized group. (I'm not citing this pride as a fault, merely a reality—I saw the same thing at many tech conferences during my Microsoft career, which people attended specifically to be first in line, so to speak, for new announcements and to mix and mingle with equally committed compatriots as well as the speakers.)

Thus, again, ask yourself whether motivational inspiration—along with any other devotionals sensibilities—is what your audience it looking for. If you’re not sure, approach such inspiration carefully or play with the edge. The same is true also of devotional sensibilities Perhaps over several stories you may develop an audience that is more ready to receive what you have to offer.

Act 3—the Climax and Conclusion

If after your questioning and soul-searching, it remains your intent to deliver motivational inspiration, then Act 3, driving to the climax and the conclusion (peroratio), is the time for it. Here, the outcome of the conflict can leave the reader with at least a sense of new possibilities in their real world rather than merely the world of the story.

Stories present possibilities to readers. Within mystical realism, that presentation means depicting states of inner awareness wherein God is real and present to ordinary people (not extra-ordinary beings) in our real world (rather than a fantasy world). Because if such awareness can be depicted with relatable and believable people in settings that reflects how our real world operates, then readers, too, might consider that such awareness is possible for themselves. That’s motivational inspiration.

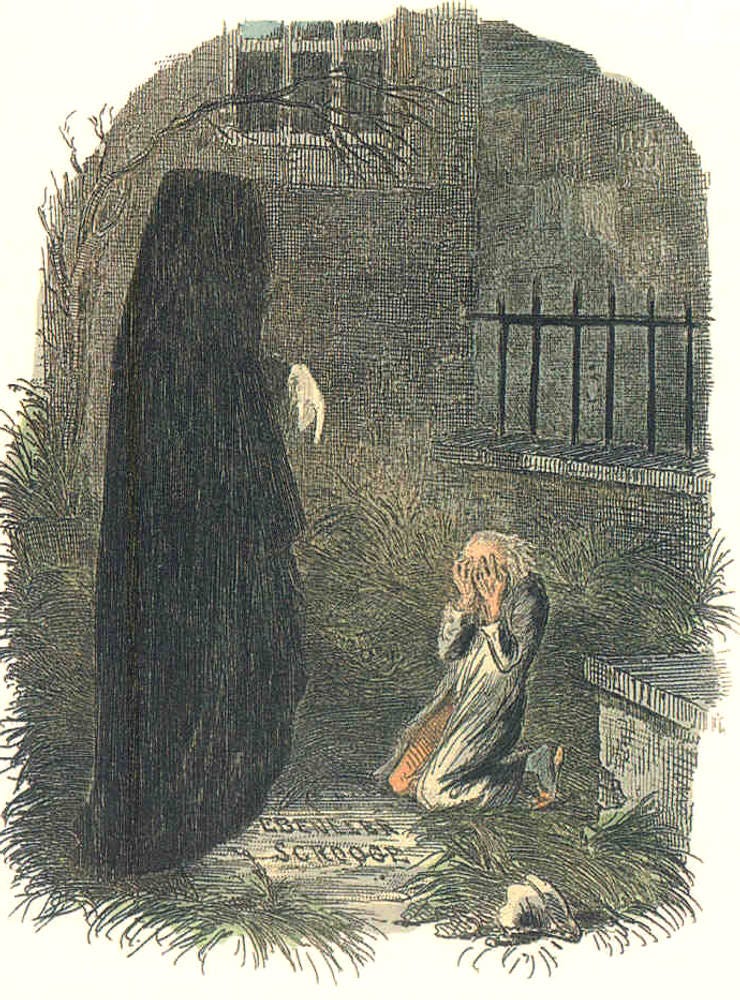

As with many “The Man Who Learned Better” stories, Charles Dickens achieves this type of inspiration in A Christmas Carol by showing readers, through the characters and situations of the story rather than exposition, the natural and inevitable consequences of certain choices. In A Christmas Carol, readers get to witness, right along with Scrooge, what happens to those who are selfish, cruel, and joyless, to those who’ve abandoned their innate charity, compassion, and love. In Stave Four, especially the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come shows Scrooge the stark contrast between the tenderness that the Cratchett’s feel with the death of Tiny Tim and the utter lack of caring that anyone has for Scrooge’s demise. Scrooge, in fact, isn’t as disturbed by death so much as he’s disturbed by idea of dying a loveless death. He realizes, finally, that love hasn’t abandoned him, it’s he who has abandoned love—something that the Ghost of Christmas Past had shown him earlier.

Stave Four gives readers the opportunity to ponder how their own choices in life will reflect upon them when it comes time to part this world. Dickens inspires readers to internalize Scrooge’s cry to the Ghost as they stand before his neglected grave:

“Men’s courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead,” said Scrooge. “But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change. Say it is thus with what you show me!” (Italics added)

“So long as you’re alive,” Dickens says to his readers, “it’s always within your power to change yourself. What, then will you do?” That’s motivational inspiration right there because change, as the Part 2 identified, is the fundamental element that sets motivational inspiration apart from the other forms of inspiration.

To drive this message home further, Scrooge declares his own passionate resolution despite the Ghost’s apparent insistence that his doom is sealed. Dickens thus gives readers an example of the kind of resolution they might make themselves, even if it’s different in the details. (In fact, just change the one word “Christmas” in the following passage to “Christ” or simply “God” and see how the passage reads.)

“Spirit!” he cried, tight clutching at its robe, “hear me! I am not the man I was. I will not be the man I must have been but for this intercourse. Why show me this, if I am past all hope?”

For the first time the hand appeared to shake.

“Good Spirit,” he pursued, as down upon the ground he fell before it: “Your nature intercedes for me, and pities me. Assure me that I yet may change these shadows you have shown me, by an altered life!”

The kind hand trembled.

“I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach. Oh, tell me I may sponge away the writing on this stone!”

In this climactic passage we can see all the elements of motivational inspiration from Part 1:

An inner clarity about the purpose of life (to keep Christmas/Christ/God in one’s heart).

An awareness of how to integrate that purpose into one’s life (practicing the lessons Scrooge has learned about compassion).

The will and courage to make the necessary decisions (the repeated use of “I will”).

As readers, we are hopefully gaining clarity, awareness, will, and courage along with Scrooge.

And even if the climax doesn’t convince us, the story’s conclusion gives us yet another chance with an additional dose of confirmational inspiration. Those scenes show how others respond lovingly to Scrooge’s changed character, which is to say, how we might also have such an experience of life if we, like Scrooge, open our own hearts.

In this regard, I particularly like the conclusion of the 1999 film of A Christmas Carol starring Patrick Stewart as Scrooge. In the final ten minutes (which is where the video below should start), notice the response of all the characters who interact with Scrooge after his inner change.

Thus, if we as readers were still on the fence after the scene in the graveyard, perhaps the conclusion, by showing such transformed interactions with others, will motivate us to reconsider Scrooge’s resolutions not just for Scrooge, but for ourselves.

Coming up

After an interim post to share a musical composition, the next one in this extended series on simplicity, inspiration, and seeking God walks through Max Lucado’s children’s book, You Are Special, to identify the kinds of inspiration that it delivers to readers at different points in the story. As a story that I claim fulfills the idea of a “simple devotional story that inspires people to seek God,” we should clearly see motivational inspiration at work as well as the other types as we’ve discussed them thus far. That walk-through will then bring us nicely to the next question, “What does it mean to seek God?”, which we’ll pick up in the new year after some Christmas-related posts in December.

Until then, your comments, as always, are welcome.

(If you like this post, bless the Algorithm Angels, the Digital Devas, or whatever you’d like to call them by selecting the “heart” icon ❤️ even if you’re not a subscriber. It helps!)