Simplicity vs. sophistication in mystical fiction, part 2

Is the goal to impress readers or inspire them?

(If you like this post, bless the Algorithm Angels, the Digital Devas, or whatever you’d like to call them by selecting the “heart” icon ❤️ even if you’re not a subscriber. It helps!)

Part 1 of this post, after looking at the question of what “attunement to modern times” means for mystical realism in fiction, discussed the important of touching the heart where inspiring readers is concerned. Here in part 2 we look at complexity as an obstacle to that inspiration and then consider what such simplicity might look like in practice.

(A note about the photo here. Part 1 spoke about childlike simplicity, and I must admit to a lifelong love of cute stuffed animals, especially as I don’t have good pet karma. The bunny in the middle, Naomi, has been my travel companion since the mid-1990s and has been to every continent except Antarctica. Cicero, the stuffed chickadee, belongs to my son and—this is his character—loves studying ancient languages like Latin and Greece, hence his full name, Cicero Aristotle Augustine. They accompanied us to Greece and Egypt in 2023 and we took opportunities to photograph them at various sites. While we were doing this at the Palace of Knossos on Crete, an Italian couple nearby exclaimed, “Oh, you have one too?” They proceeded to reveal Bambo, the panda, whom they’d acquired at the San Diego Zoo for the same purpose. We all thought it was sweet to capture a moment of making new friends.)

Complexity as an obstacle to inspiration

When seeking to write spiritually inspiring stories, as discussed in Part 1, simplicity is the doorway to touching and inspiring the hearts of readers.

Of course, if your goal as writer (or musician or artist) is not to inspire people but to impress literary critics, then you should weave as much complexity as you can into your stories and give critics and readers alike an intellectual challenge of trying to figure out what it all means.1

I recently listed to a few episodes of the Literary Life podcast in which the hosts delved into the many literary layers of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. It was fascinating to learn about the degrees to which J. K. Rowling built upon the traditions of medieval romances in her work and wove in all kinds of subtle symbolism. What struck me most, though, was how the hosts raved about Rowling as an author. They praised her sophistication, called her a “master of structure,” and referred to her several times as a “genius.” Along those same lines, the hosts also demonstrated their own expertise by calling out literary devices, identifying symbols, explaining allegories, unraveling allusions to myths and legends, and making connections to other classic literature. Like I said, it was all quite fascinating.

What also struck me is that for all this, they said next to nothing about what the story might mean to readers in terms of inspiration. At best, they mentioned that the story depicts the generic “soul’s journey back to God,” but they never considered whether the story, for all its literary elegance, would actually inspire readers to want to make such a journey for themselves. I got the impression that they seemed wholly satisfied, even as people of faith, that said “journey” merely exists in the abstract.

I’m not saying that any of this is wrong; talking about reader inspiration perhaps doesn’t fit into their podcast. And learning to “read with new eyes,” as the hosts called it, and to grasp all the intricacies is the very foundation of literary analysis, literary criticism, and, for writers, literary sophistication. It’s also quite pleasing to the intellect and the ego, and if it gets people to actually read books, all the better!

But here’s the question that concerns us here with Deus in Fabula: does such literature leave readers inspired?

Spiritual inspiration, as stories of mystical realism would, I think, seek to deliver, is a matter of touching readers’ hearts to encourage them to make different choices than they’ve made in the past—ideally choices to expand their sympathies and attunement to God. Whether anyone is impressed with you as an author is beside the point, and thus there’s really little need for complexity and finesse.

So too with complexity that’s designed merely to delight the reader’s ego, which is the feeling I get from heady novels like Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum. If the goal of mystical realism in fiction is to inspire readers to seek God, then building up the ego is counter-productive: the bigger one’s ego, the less space there is for God. As Jane Tyson Clement wrote in her poem, “The Gate”:

If you would enter, traveler,

into this city fair and wide,

it is forever and you leave

all trappings of the self outside.2

If you want to indulge in pride and self-satisfaction, then God, though omnipotent, humbly retires to the background. When your desiccated heart finally aches once again for love and opens to Him in childlike trust, He’ll be there without anger or wrath, just like the father of the prodigal son who celebrates the return of his wayward child.

Simplicity in practice: writing the children’s version

What, then, does simplicity mean for fiction? I think it primarily means intent more so than any specifics about story length, plot arcs, characters and archetypes, and so forth. If your intent is to impress readers with your brilliance, then I think you’re naturally drawn to complexity—the literary equivalent of composing music with six-part harmonies, mixed timings, and Bach-esque key modulations. If your intent, however, is to leave readers with inspiration and with an awakened sense of greater possibilities for themselves, then I think you’ll naturally look for the simplest way to accomplish that goal, like composing melody-only song, rather than cloud it with extraneous noise.

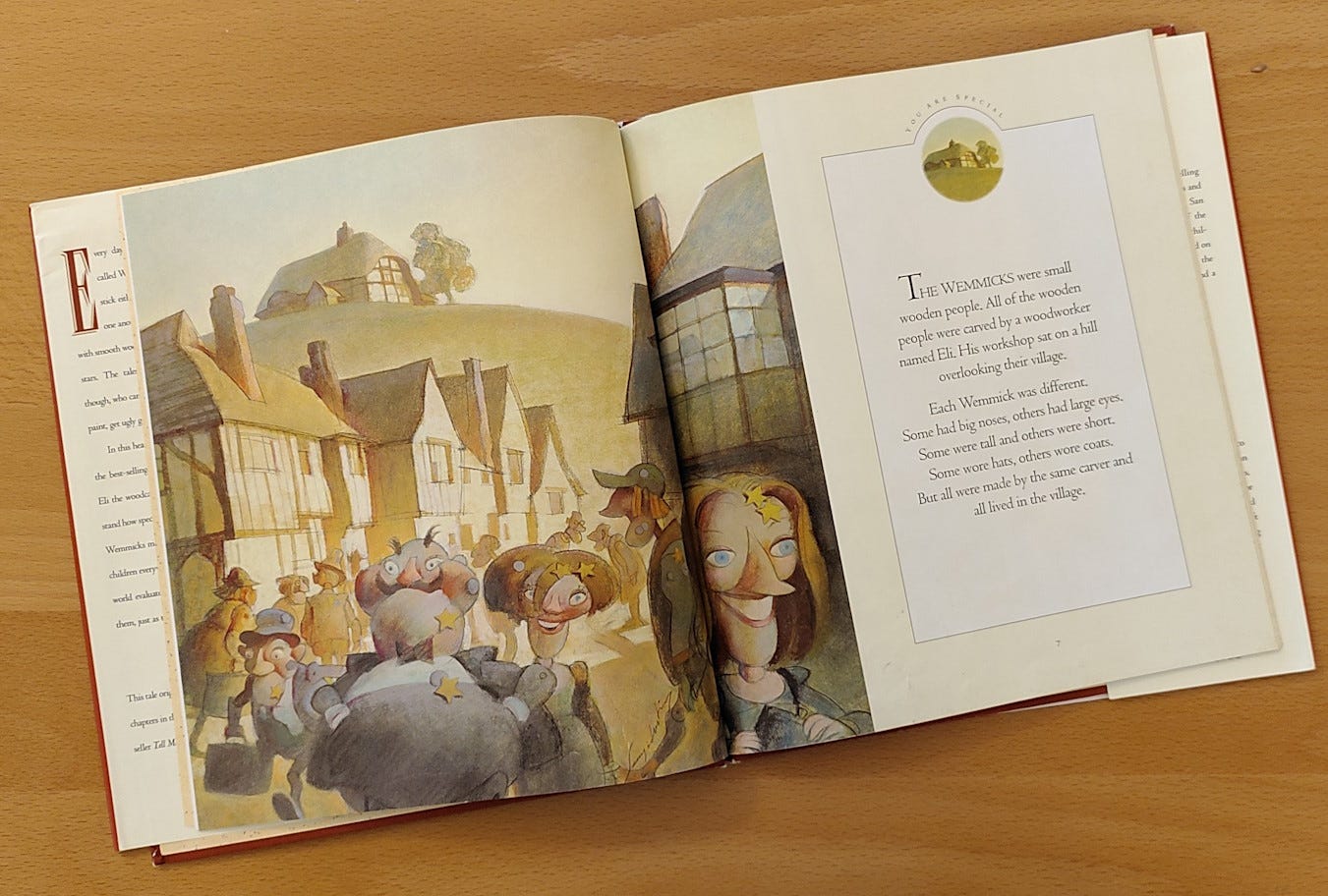

With this approach in mind, children’s books can provide examples of clear, purposeful, and simple storytelling. Consider Max Lucado’s story about Punchinello in You Are Special, which I wrote about in Genuine spirituality in fiction, part 1 and consider to be a “simple, devotional story that inspires people to seek God.” Even though the setting is something of a fantasy world with the Wemmicks being wooden people created by the woodcarver Eli, it’s wholly relatable because the Wemmicks so clearly represent humans and Eli clearly represents God.

The Wemmicks clearly illustrate typical human behavior in our tendency to judge each other based on worldly standards of success and failure. The message of the story is that such measures don’t matter to God in the least. He loves each of us regardless and the more we focus on Him, the less we, too, will worry about the world’s judgments.

This is an inspiring story because it leaves readers—adults, certainly, and likely also children—with a desire to find ways to spend time with God in their real lives. And it’s certainly simple because it can be expressed as a children’s story.

The same story could also be expressed as a full novel: expand each page into a chapter or two, building up the characters and the situations as well as giving the imagery that the children’s book has in the illustrations. 32 pages expanded to 2500 words each is a 96K novel.

Why would you write such a novel instead of a children’s book? Because a novel offers young adult and adult readers much more time to spend with the thoughts and especially with the feelings of the story. It could also provide many more specific and relatable examples of how we get so wrapped up in “success” and “failure” and forget God in the process. That increased time and greater relatability could then deepen the inspiration beyond what a children’s book might accomplish for the same readers.

In both bases, the core “story” is the same. Which is to say, stories don’t have to be more complicated than this at their heart. To test the simplicity of a story, try to write the children’s book version in around 750 words or less. If you can do that clearly, then you understand what the story is really about.

Simplicity in practice: avoiding complexity pitfalls

With a clear and direct story in mind, a sincere intent to inspire readers, means, in large part, avoiding temptations to introduce complexities that would distract readers from the central story line. Again, these complexities, which is much of what characterizes literary sophistication, might gain a few lines of praise in literary and customer reviews, but they won’t touch readers’ hearts.

Here are a few thoughts:

Stick to the main story; keep subplots and subtexts to a minimum if you need them at all. Take a lesson from movie editors and ruthlessly cut anything that pulls one away from the primary storyline.3

Stick to the clear meaning that you’re trying to convey without guile, ulterior motives, or hidden agendas. (Consider that sophistication is related to sophistry, which is “subtly deceptive reasoning or argumentation.”)

Write in relatively plain language (appropriate to your authorial voice) so that your wordcraft doesn’t compete with the story and the inspiration it can deliver.

Don’t play tricks on the reader or employ intellectual cleverness for the sake of being clever. (You can play tricks on characters, of course, but that’s different from messing with the reader.)

Use symbols and allegories sparingly; don’t try to “blow people’s minds” by weaving a tangled tapestry in the vague hope that readers will somehow discover hidden connections that you yourself don’t understand.

Most importantly, be attuned to your own sense of inspiration, to your own connection to the Divine, and pray to be able to help readers, through your art, make that connection for themselves. In that way the story becomes applicable to their lives in personally meaningful ways.

And if, in the process, they forget about you as the author, all the better! After all, if you’re sincere about inspiring readers to seek God, why would you wish to be on any kind of pedestal that competes for the reader’s devotion?

(If you like this post, bless the Algorithm Angels, the Digital Devas, or whatever you’d like to call them by selecting the “heart” icon ❤️ even if you’re not a subscriber. It helps!)

Which people do even when an author explicitly states that a story has no hidden meanings whatsoever. In the foreword to Watership Down, Richard Adams flatly states that the book is nothing more than a story about fuzzy rabbits that he made up to entertain his children on long car drives. Tolkien, too, said that The Lord of the Rings was in no way an allegory. Yet people nonetheless write dissertations to make such claims.

The Secret Flower: and other stories, page 162 of the Kindle edition.

But save that material; if the story is successful, you can create a special extended edition, as was done with The Lord of the Rings movies.