In my “quest for spiritual, devotional, and mystical realism in fiction” (the tagline of Deus in Fabula) I’ve been reading a wide variety of fictional works not only to (hopefully) find examples of what I’m looking for, but to also better understand what, exactly, I’m looking for. As I mentioned in Mystical realism: Motivations, inspirations, and opportunities, this search began with the question of whether anyone today was writing “spiritual novels” and “simple, devotional stories that inspire people to seek God.”

In previous posts, too, I’ve hopefully made clear what I mean by “mystical” (see Mythical, Magical, and Mystical) and “devotional” (see Emotion, “Inpletion,” and Devotion, part 2) as used in the tagline. What I haven’t yet done, however, is delve into the “spiritual” part.

It’s time to open that proverbial can o’ worms, then. I refer to it as such because various ideas about what constitutes “spiritual” and “spirituality” seem to be all over the map. Much, of course, relates to religious sensibilities, as I’ve understood “spiritual” to mean for all of my adult life. But then there’s also such a thing as “secular spirituality” (an oxymoron if I ever heard one), arising, I think, from the growing number of people who identify as “spiritual but not religious.” Similarly, I’ve also heard that there are atheists who yet consider themselves “spiritual.”

Clearly, the term has become rather muddled, which is why I hesitated to even include it in the Deus in Fabula tagline at all. Yet I can’t just dispense with the word either, because there’s much of value that yet shelters under its wings.

It’s necessary, then, to delve into the matter and find a genuine spirituality that is neither too restrictive in the religious sense nor denatured in the secular sense. True or genuine spirituality, in my mind, should be a powerful, life-altering quality or experience, not something that’s watered down to the point where it’s merely decorative.

I’ve titled this post with “part 1” not knowing exactly how many parts will be involved, but I know it’ll be more than one!

“Spiritual” as defined by publishing categories

As a starting point, let’s consider how the publishing and bookselling industries categorize different books that might be termed “spiritual.” In Mystical realism: Motivations, inspirations, and opportunities, I mentioned that when I first began looking around for spiritual novels I found that sources like Goodreads, Amazon, and WorldCat have lists of “spiritual fiction” and also books they classified as “spiritual but not religious.”

Right away, however, I noticed some curious characteristics. For one thing, many titles on these lists aren’t fiction at all. Second, they omit much of what is separately classified as “Christian fiction.” The works of C.S. Lewis, for example, do not appear on the “spiritual” lists, even though they are deep, spiritual allegories. I noticed, too, that two of my favorite fiction titles, The Song of Bernadette and The Robe (both works of historical fiction) are also missing, as are classics like Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ by General Lew Wallace, The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene, and The Keys of the Kingdom by A. J. Cronin, among many others.

Apparently, “spiritual” and “Christian” are mutually exclusive where literary categorization is concerned, suggesting even that “spiritual” is a euphemism for “non-Christian.” I find such distinction or separation unnecessary, because although plenty of Christian works are little more than fictionalized sermons (which is equally true even of many non-Christian “spiritual” titles), there are yet many stories, like C. S. Lewis’s works, that I believe can be inspiring and uplifting for people of any faith because they are more universal than sectarian in nature.1

The other curious feature of these lists of “spiritual fiction” is their definition of “spiritual” is, shall we say, rather generous. In my mind, spirituality should have at least something to do nonmaterial realities, namely God (or some other Absolute, like the Ultimate Reality of the Buddhists) and/or the idea of the soul as distinct from the physical body. It doesn’t even need to be explicit in that sense: a story can certainly inspire and uplift a reader with attitudes that are attuned to such higher realities. One can relate to God, for example, though transcendental qualities like love, peace, calmness, joy, wisdom, light, truth, beauty, and goodness without ever labeling them “God”—for if there’s a sense of expansiveness in that relationship, and especially a sense of transcending the ego, then one is moving toward a greater spiritual understanding.

Various titles on those lists do meet those criteria, ones that are on my reading list and that I hope to report on in the future. Others—perhaps many (and I’ve admittedly examined only a small percentage of them)—seem merely psychological or wholly materialistic. To illustrate this, let me offer a couple of examples that strike me as somewhat lacking and then contrast those with a non-sectarian story that is truly spiritual.

Example #1: When We Believed in Mermaids

When We Believed in Mermaids by Barbara O’Neal appears on Goodread’s “spiritual but not religious” list. Now, because I only paged through this novel and didn’t read it in detail, my comments here have nothing to do with its content or quality as a novel. From the reviews, it appears to be very popular and well-written, with over 151,000 ratings on Amazon and over 226,000 on Goodreads (those are huge numbers).

What I’m specifically curious about is why the novel appears on a list of “spiritual” works at all. For one thing, it’s categorized on Amazon as Mystery Romance, Sisters Fiction, and Contemporary Women’s Fiction—not that those genres couldn’t have a spiritual flavor, but I didn’t see anything in the book that is clearly spiritual in the sense of relating to a greater reality of any kind. Indeed, neither the synopsis nor various reviews suggest anything of that nature (even in allegory). Here’s the synopsis from Amazon:

Josie Bianci was killed years ago on a train during a terrorist attack. Gone forever. It’s what her sister, Kit, an ER doctor in Santa Cruz, has always believed. Yet all it takes is a few heart-wrenching seconds to upend Kit’s world. Live coverage of a club fire in Auckland has captured the image of a woman stumbling through the smoke and debris. Her resemblance to Josie is unbelievable. And unmistakable. With it comes a flood of emotions―grief, loss, and anger―that Kit finally has a chance to put to rest: by finding the sister who’s been living a lie.

After arriving in New Zealand, Kit begins her journey with the memories of the past: of days spent on the beach with Josie. Of a lost teenage boy who’d become part of their family. And of a trauma that has haunted Kit and Josie their entire lives.

Now, if two sisters are to reunite, it can only be by unearthing long-buried secrets and facing a devastating truth that has kept them apart far too long. To regain their relationship, they may have to lose everything.

This synopsis suggests that the story deals more with psychological matters. One review on Amazon even notes the distinct absence of what I’d consider to be basic spirituality:

[O’Neal] is a great writer and I feel captured by her style. I wish there was some indication of belief in God. That would make her stories so much more powerful and meaningful.

Other reviews further underscore the psychological nature of the story. Here’s a representative one:

Overall, this was a wonderful, very engrossing story, with strong themes of familial love, forgiveness, and redemption. It’s also a story about finding inner strength, owning one’s mistakes, resilience, personal growth and love’s power to heal broken relationships. While there are some serious issues explored in this novel, ultimately, it is an uplifting, satisfying book….

This is all good stuff, and I’m delighted that people find the story uplifting, which I certainly prefer to fiction that leaves you sad or depressed.

With this sense of upliftment, the novel could be described as “inspiring," which one might deem a kind of spiritual quality, especially a quality of secular spirituality. It may even inspire readers in a moral sense to forgive other family members and to seek reconciliation. But does it inspire readers to deepen their connection to God, whether in a personal or impersonal sense? I think the answer is “no.” Similarly, is the “power of love” noted in the review above speaking to God’s love or merely human love? Love is a good thing, but the book seems to deal with human love only, in which case it’s on the same level as the theme song in Back to the Future called “The Power of Love.”

As such, I have to classify the book more as a psychological story than a clearly spiritual one because in the end I don’t see it inspiring readers to even consider God’s presence in their lives, let alone develop a deeper devotion to God.

(Note: all that said, such a story, and really any story that involves positive qualities, can have a spiritualizing effect on certain people. I will address this aspect of spiritual effect in a future post.)

Example #2: Aldous Huxley’s Island

Aldous Huxley’s 1962 novel, Island, which appears on Goodread’s list of “spiritual fiction,” is a utopian manifesto that complements his more well-known dystopian work, Brave New World, written three decades earlier. Island, which I have read, isn’t really a novel: there’s very little in terms of a plot. Instead, the book is mostly filled with lengthy conversations in which people expound various philosophical points—hence the characterization of the book as a manifesto. It also contains lengthy “excerpts” from other books that exist only within the story, which are themselves given the status of pseudo-scripture.2

For example, several pages in Chapter 5 are passages from a fictional book of philosophy entitled Notes on What's What, and on What It Might be Reasonable to Do about What's What. Here’s one of the passages:

Faith is something very different from belief. Belief is the systemic taking of unanalyzed words much too seriously. Paul's words, Mohammed's words, Marx's words, Hitler's words—people take them too seriously, and what happens? What happens is the senseless ambivalence of history—sadism versus duty, or (incomparably worse), sadism as duty; devotion counterbalanced by organized paranoia; sisters of charity selflessly tending the victims of their own church's inquisitors and crusaders. For Faith is the empirically justified confidence in our capacity to know who in fact we are, to forget the belief-intoxicated Manichee in Good Being. Give us this day our daily Faith, but deliver us, dear God, from Belief.

Although this material properly distinguishes untested belief from faith born of actual experience, it’s rather cringeworthy. To me it also reflects that much of Huxley’s worldview in Island is based on his experiments with psychedelic drugs dating back to the mid-1950s, which also factor into the “spiritual” experiences of the novel’s characters. But such drug-induced experiences don’t seem to have anything to do with an expansion of consciousness or an expansion of sympathy for others, let alone increasing a person’s devotion to God.3

Island continues to quote at length from this same text in subsequent chapters, and although there are other discussions related to “spirituality,” there is yet no transcendence to be had. As with When We Believed in Mermaids, even though some readers may find it inspiring to a degree, there’s yet little here to inspire a reader toward genuine spiritual development. In the end, Island actually strikes me as quite materialistic.

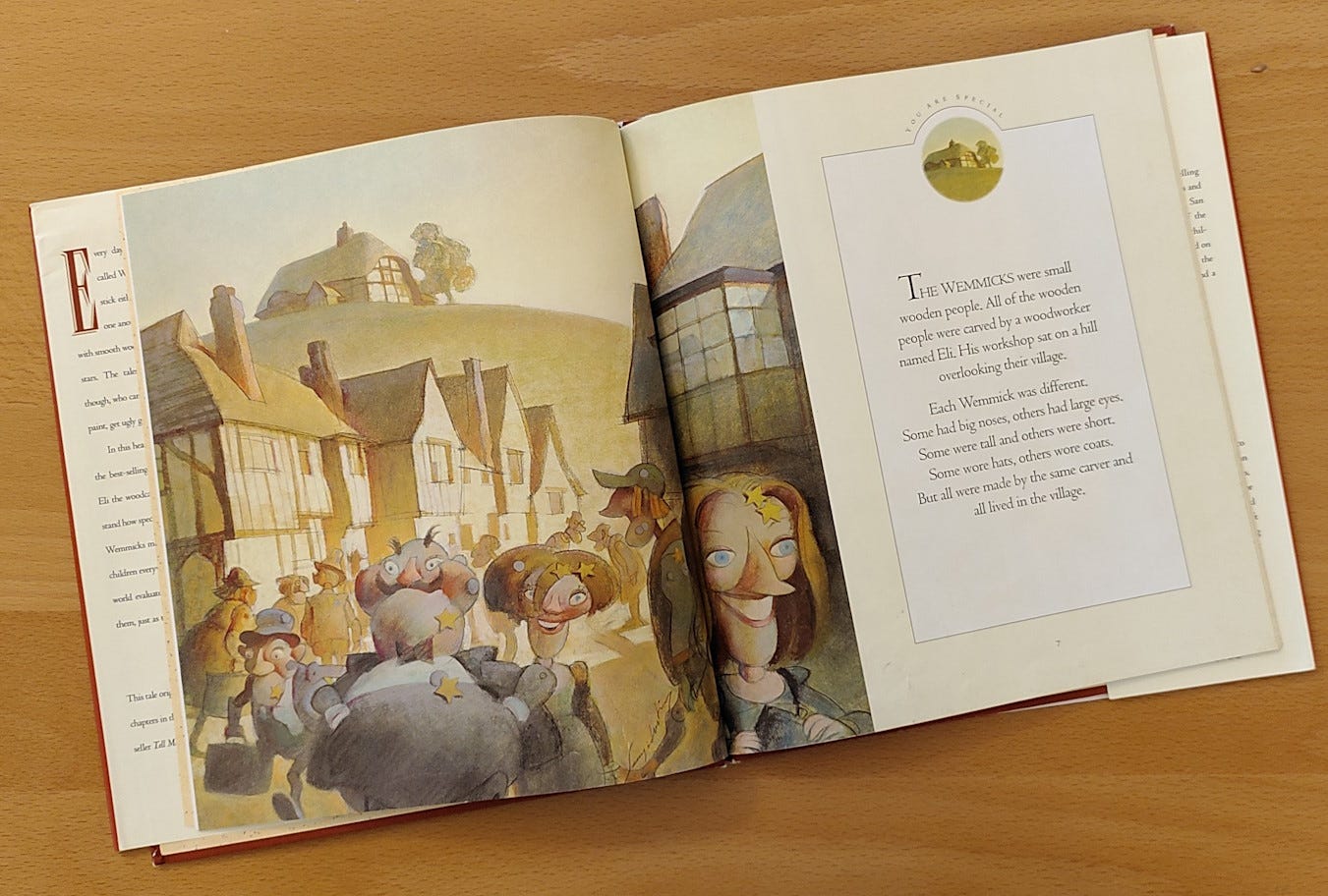

Example #3: Max Lucado’s You Are Special

The final example I want to offer in this post is the children’s picture book You Are Special by Max Lucado (who is a widely acclaimed minister and prolific author in San Antonio, Texas). As a children’s book I wouldn’t expect You Are Special to appear on lists of otherwise adult fiction, and even if it did it’d likely be relegated to a “Christian” list. Yet, I consider it to be beautifully spiritual in that it inspires a greater devotion to God in a non-sectarian manner without making any explicit statements to that effect.

The main characters in You Are Special (which, by the way, our son asked my wife and I to read at bedtime every night for probably four years) are wooden people called Wemmicks, made by the woodcarver, Eli, whose workshop sits on hill above the Wemmicks’ village.

Here’s the synopsis from Amazon:

In the town of Wemmickville there lives a Wemmick named Punchinello. Each day the residents award stickers―gold stars for the talented, smart, and attractive Wemmicks, and gray dots for those who make mistakes or are just plain ordinary. Punchinello, covered in gray dots, begins to feel worthless. Then one day he visits Eli the woodcarver, his creator, and he learns that his worth comes from a different source.

To be more precise, at the nadir of his self-worth, Punchinello meets a Wemmick named Lucia who, to quote the book:

… was unlike any he’d ever met. She had no dots or stars. … It wasn’t that people didn’t try to give her stickers, it’s just that the stickers didn’t stick.

Punchinello, inspired by this possibility, asks Lucia how she does it. She replies:

“It’s easy. Every day I go see Eli, the woodcarver. I sit in the workshop with him.”

Punchinello is initially afraid to call upon his creator because he’s worried that Eli won’t want to see him, covered in dots as he is. But mustering the courage to climb the hill, he learns that Eli sees things quite differently:

[Eli] “I don’t care what the other Wemmicks think.”

[Punchinello] “You don’t?”

[Eli] “No, and neither should you. … What they think doesn’t matter. All that matters is what I think. And I think you are pretty special.”

A little later Eli says,

“The more you trust my love, the less you care about their stickers. … Remember, you are special because I made you. And I don’t make mistakes.”

Punchinello isn’t sure he understands, but he opens himself to Eli’s love. As the story concludes:

In his heart he thought, I think he really means it.

And when he did, a dot fell to the ground.

As you can see, there’s nothing in the synopsis or the story as a whole that’s explicitly religious or even spiritual—it never says that Eli represents God and the Wemmicks represent us. You’re free to infer that, or not. But the underlying message is clear: the more you spend time with God—or simply with someone who loves you unconditionally—the less you need to worry about what other people think of you. Your worth as a human being is rooted in the singular fact that you are God’s child.

You Are Special thus leaves readers with a deeper connection to God because just about every reader can identify with Punchinello’s plight and likely has a deep desire to find a basis for self-worth that goes beyond worldly or material success. It easily inspires a reader to ask, “How might I spend a little time with my Creator (God) every day, like Punchinello? What does it mean to go up the hill to the workshop?” That can mean anything from prayer and meditation to singing or taking a walk with God in nature to serving others or just working on keeping your thoughts and feelings more elevated. You might make a conscious decision to listen to more uplifting music, to limit your exposure to the negativity of news and the sensual assault of advertising, or to learn a little patience and give others the benefit of the doubt. The applicability is really quite endless, and whatever a reader chooses to do along these lines will draw him or her closer to God.

You Are Special, in short, is a clearly spiritual story because it points to God and serves to uplift a reader’s awareness toward God in a way that a merely psychological story like When We Believed in Mermaids and a faux-spiritual story like Island does not.

Coming up

In the introduction to this post I said that genuine spirituality should be a powerful, life-altering experience. The examples of When We Believed in Mermaids, Island, and You are Special demonstrate the difference between a psychological story, a faux-spiritual philosophical story, and a truly spiritual story. It hardly needs saying that when I speak of seeking spiritual fiction or spiritual realism in fiction, I’m really looking for stories like You Are Special that, through its easy applicability, inspire a reader to seek God, in their real lives. That’s the “realism” part.

The next post on this subject will examine the notion of “spiritual but not religious” and why that identity tends to pull people more toward the secular than the genuinely spiritual. In the end, though, I think even that circuitous route eventually leads one back to matters of God and the soul.

Until then, comments are welcome!

It’s worth noting that the “Christian” label in publishing is something of a marketing term that identifies an intended audience rather than an indicator of specific content. That there is a genre of “Christian fantasy,” for example, says a lot in and of itself, because stories set in other worlds clearly aren’t going to involve the Bible, Jesus, or other aspects of earthly religion. In another sense, the label acts something like a content rating to assure potential readers that the book respects Christian values and doesn’t contain material considered offensive to Christian sensibilities, such as gratuitous profanity or graphic depictions of sex and violence. As such, spiritually-minded non-Christians who also prefer “cleaner” content can enjoy Christian fiction provided it’s not overly dogmatic, sectarian, or preachy.

I’m suspicious any time a so-called “novel” quotes at length from some other supposed tome of truth because it almost surely indicates that the book was written less as a good story and more as a vehicle for the author’s agenda in the real world. Some of Marie Corelli’s novels contain pages of such passages, which I find tiresome because she was clearly using them to expound her own spiritual philosophy as an author. Another such example is The Celestine Prophecy by James Redfield, which is clearly a New Age treatise disguised as fiction and with which Redfield established himself as a “spiritual” teacher. Indeed, from what I can see on Redfield’s website, www.celestinevision.com, he promotes The Celestine Prophecy as a new scripture even though it’s entirely psychological in nature (that is, there’s no mention of God or devotion to God anywhere—it’s actually all about ego). And people take him seriously enough that he has to explicitly state that the “manuscript” in the story is entirely fictional, even while he sincerely believes in the “teachings” he wrote into it.

According to Wikpedia’s article on The Doors of Perception, the book in which Huxley documented his psychedelic experiences, “Huxley's friend and spiritual mentor, the Vedantic monk Swami Prabhavananda, thought that mescaline was an illegitimate path to enlightenment, a ‘deadly heresy’ as Christopher Isherwood put it.”