Emotion, "inpletion," and devotion: part 2

The power of devotion to transcend emotional disturbances and emotional exhaustion

In a previous post I shared an excerpt from my draft novel entitled A Gift for King Felix in which the protagonist, a young shepherdess named Ba, is flogged for bringing false accusations against others in her village. For the sake of the story, I had to inflict that pain upon her. (When I told my wife about this and other scenes in which Ba suffers, she sympathetically exclaimed, “Poor Ba!”).

Consequently, I had to inflict something of that pain upon myself as an author, as many authors must do with their own characters. And like I’ve said, such self-inflicted suffering takes its toll and is considered by many an unavoidable consequence of writing fiction. To make matters worse, we often try to offset one emotional extreme with an equal extreme on the other side of the emotional spectrum—to balance pain with pleasure, depression with excitement, and anxiety with bold confidence. Yet doing so is exactly what puts one at risk of emotional exhaustion due to the never-ending intensity.

The concept of inpletion, as introduced in part 1 of this series, offers a different approach: instead of swinging to the opposite emotional extreme, thus amplifying the overall energy, relax into a place of stillness. This is what I sought to do in the scene with Ba by giving her a vision of Christ that brings her to a deep peace. That’s also what I wrote in my account, A Matter of the Heart.

But in both stories there’s something more: a reaching upwards toward the divine not through emotion, but through devotion, which is possible only at that calm center of inpletion. As Psalm 46:10 puts, it, “Be still and know that I am God.”1

Devotion, in other words, is built upon a foundation of inpletion, making inpletion an essential aspect of the mystical realism that I’m looking for in fiction. Without that internal direction, much of what passes for “devotion” is merely emotionalism painted over with a veneer of what appears to be “spiritual” or “religious.”

A demonstration of the nature of devotion

As a means of demonstrating something of the nature of devotion in relation to emotion, let’s do a little craft project.

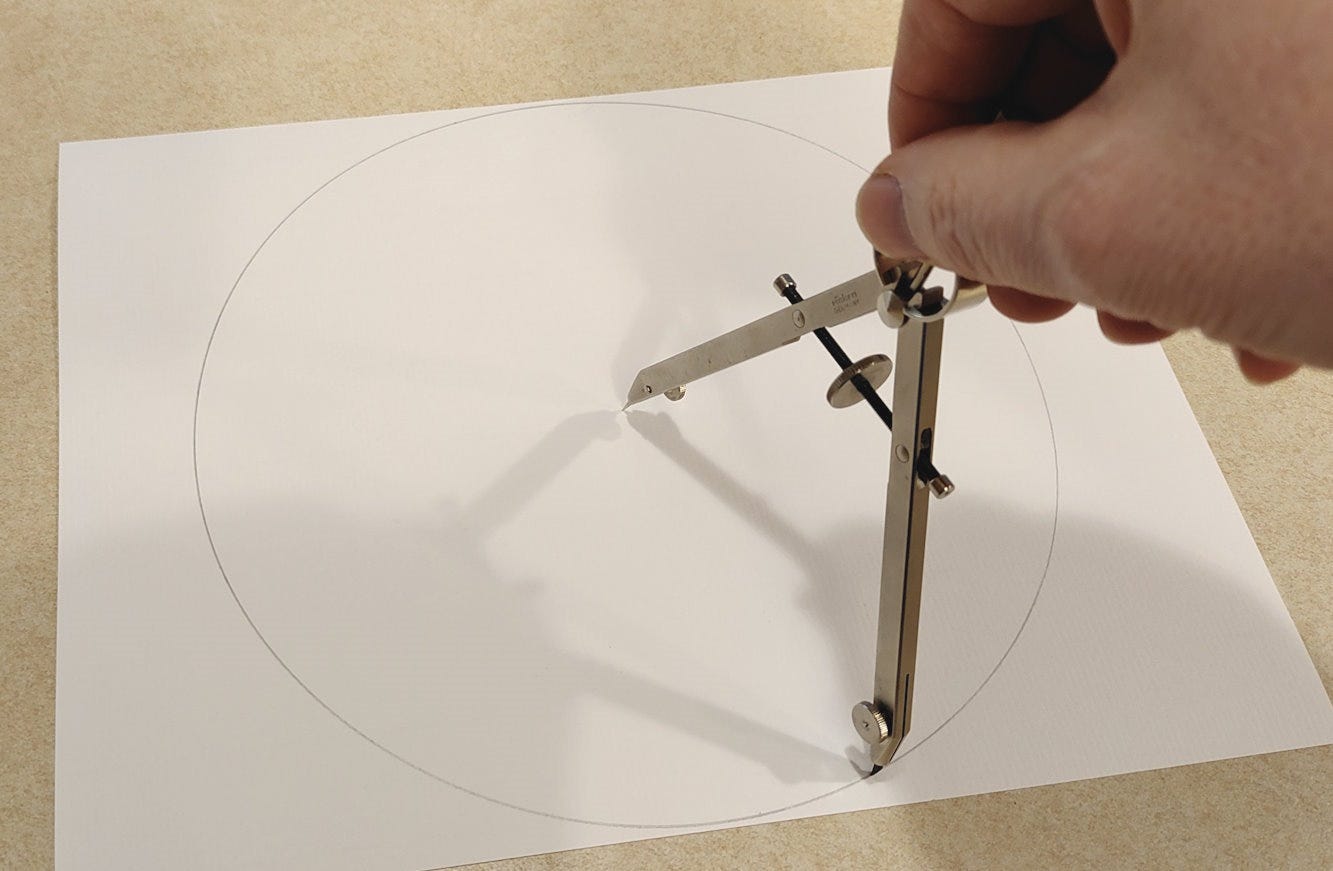

On a piece of cardstock (or a part of a cereal box), use a compass to draw a large circle. A compass is helpful because it also leaves a mark at the center of the circle.

Next, cut the circle out of the paper and try to balance that disc on the tip of a pencil. Although it’s possible, it’s very difficult; you might have to resort to using the eraser end of the pencil to keep the disc there even for a short time. Either way, the disc is very unstable—any little tap or the least puff of wind knocks it off the pencil.

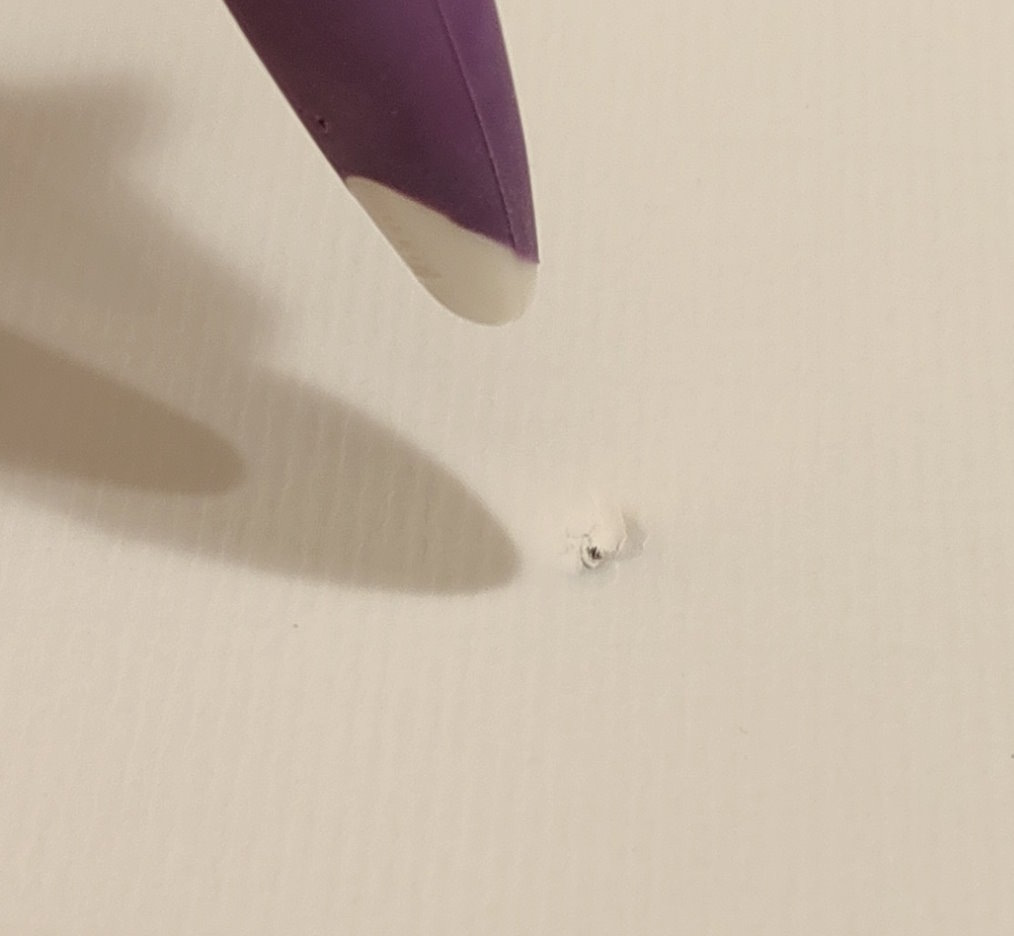

Now create a small dimple (a millimeter or two is fine) at the center point of the disk by pressing it with something blunt like the tip of a toothbrush handle or a ballpoint pen cap. It works best to have some material under the paper with a little give, like a towel, a blanket, or your fingertips.

Now try to balance the disc on the pencil again. Notice how even that tiny dimple makes it much easier to balance the disc. The disc is also more resilient to disturbances.

You might already see where I’m going with this but let me make it clear. The disc represents the plane of emotional experiences, and even though it’s possible to find a bit of balance at the center point of inpletion, the whole situation is yet very delicate. But raise those calm feelings up even a little above the emotional plane and there’s much greater stability.

But how, exactly, do we raise our feelings in this way? Truth is, we can’t do it by self-effort alone, as St. Paul is so often quoted as saying (Ephesians 2:8-9), because the power that makes the dimple—the power for upliftment—is God’s grace. But that doesn’t mean there’s no effort involved: to be lifted by grace, we have to cooperate with it. That’s a big part of devotion. We have to actively attune to grace and be receptive to it and allow it to lift us, to allow it to make that dimple.2

In the Bhagavad-Gita, Krishna says, “even a little practice of this inward religion will free one from dire fears and colossal sufferings,” (II:40) including the stormy turbulence of emotionalism and the subsequent exhaustion.

“Come further up, come further in”

In The Last Battle, the final book of The Chronicles of Narnia, C. S. Lewis made a similar comparison between the old Narnia, considered “an imperfect and corruptible shadow,”3 and the New Narnia, which symbolizes heaven. The comparison is a suitable analogy for transcendence of the emotional plane through devotion.

And the sea in the mirror, or the valley in the mirror, were in one sense just the same as the real ones: yet at the same time they were somehow different — deeper, more wonderful, more like places in a story: in a story you have never heard but very much want to know. The difference between the old Narnia and the new Narnia was like that. The new one was a deeper country: every rock and flower and blade of grass looked as if it meant more. I can’t describe it any better than that: if ever you get there you will know what I mean.

It was the Unicorn who summed up what everyone was feeling. He stamped his right fore-hoof on the ground and neighed, and then he cried:

“I have come home at last! This is my real country! I belong here. This is the land I have been looking for all my life, though I never knew it till now. The reason why we loved the old Narnia is that it sometimes looked a little like this. Bree-hee-hee! Come further up, come further in!”4

And what is the effect of that “further in” (inpletion) and “further up” (devotion + grace) that lifts one even higher above the emotional plane than that first little dimple in our disc? That’s easy to demonstrate.

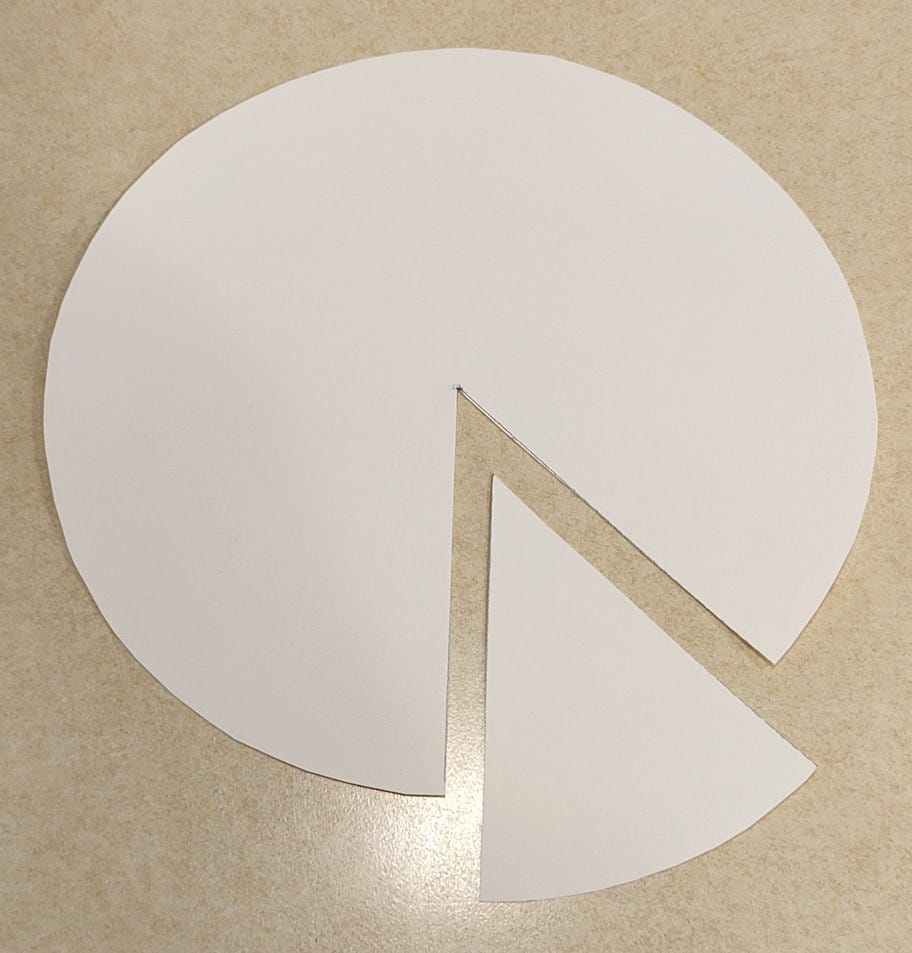

On your disc, use a straightedge to draw two lines from the edges to the center so you can cut out a wedge, like you’re cutting a slice of pizza.

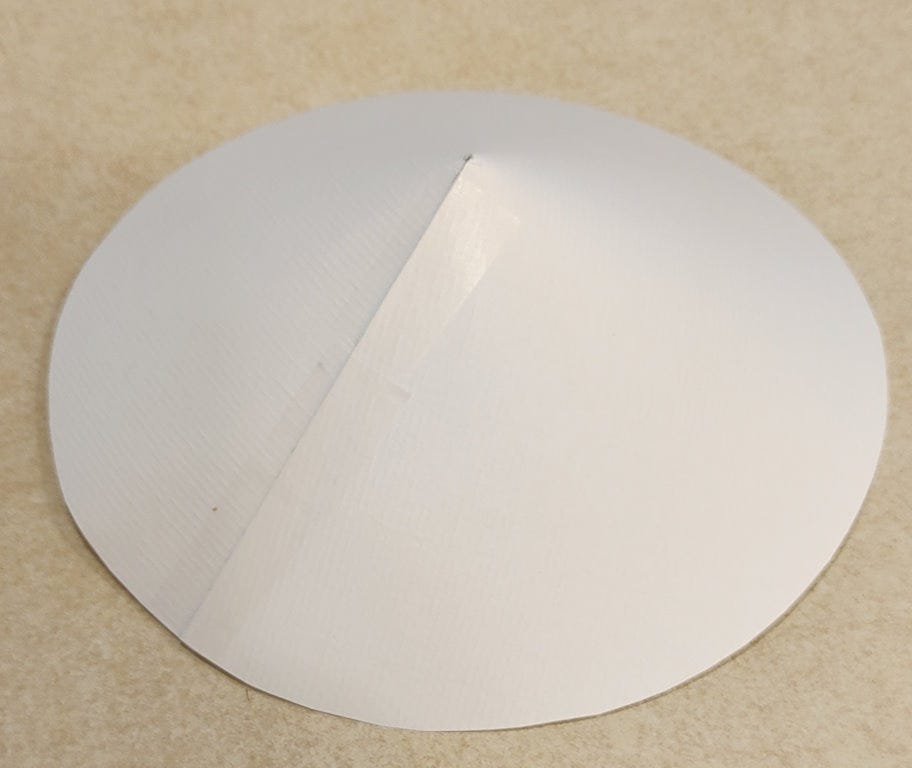

Curl the disc and tape the open edges together to make a cone:

Balancing the cone on the pencil is now effortless, so much so that you can jiggle it all over the place without having it fall off (as shown in the video below—there is no sound). What’s more, the cone naturally recovers itself to a point of equilibrium, even if the cone is a little irregular.

The unbreakable resilience of devotion

The simple conclusion of this demonstration is that the greater the uplift—that is, the more we allow grace to lift us above emotional plane—the more we are able to withstand any kind of emotional turmoil. With that uplift, both balance and equilibrium (as shown in the video) become natural and automatic.

People who, as I mentioned in part 1 of this series, deliberately practice inpletion through methods like centering prayer and meditation, and from that point direct their awareness toward God in devotion,5 find themselves becoming more and more resilient to emotional disturbances, more and more able, as Paramhansa Yogananda put it, to “stand unshaken amidst the crash of breaking worlds.”

In fact, to refer back to our demonstration, there’s a point at which the cone becomes tall enough compared to its diameter that it’s impossible to knock the cone off the pencil. And the people who have reached that point, spiritually, are those we call saints.

Consider again Bernadette Soubirous in The Song of Bernadette, who is a static arc character because she doesn’t undergo change. Her story is rather about how her utter devotion to the Lady makes her impervious to every persecution levied against her whether personal, institutional, secular, or clerical.

Author Franz Werfel notes this imperviousness even during the initial encounter with the Lady in Chapter 7. He describes Bernadette’s inner response as follows:

First Bernadette feels a brief quivering pang of terror, next a steady fear. But this is no familiar fear, no fear that impels one to jump up and run away. It is as though someone softly clasped forehead and breast in an embrace and one desired this embrace to last and last.

Bernadette’s response here is not emotional, specifically because it’s not a “fear that impels one to jump up and run away.” Instead, her response is inpletional: she’s locked in an embrace of perfect stillness. And note the last phrase: “one desired this embrace to last and last.” That’s the uplift, the devotion, the inner surrender to the divine.

The next passage then describes how this devotion transcends any and all emotional concerns:

Later this fear melts into still another feeling of which this child Bernadette has no idea and can find no name. One might call it comforting or consolation. But until this instant Bernadette never knew that she was in need of being comforted. For she is really not at all aware of the hardness of her life: that she suffers hunger, that she is housed with five other people in the dark hole of the Cachot, that she passes long nights struggling for breath. This has always been so and will probably always be so. This is naked reality accepted as a matter of course. But moment by moment now she is more deeply swathed in this consolation which has no name, which is a hot flood of compassion. Is it a compassion that Bernadette feels for herself? That, too. But the self of this child is now so cleft asunder, so open to the universe and so at one therewith, that the utter sweetness of this compassion penetrates her [entire being].

Later, in Chapter 20, we read another passage that speaks to how Bernadette had no space in her consciousness for any lesser concerns, such as what people thought of her and whether or not they believed in her visions:

Bernadette did not lose [her spontaneity to fame]. Her innocence in this matter of success, was, to be sure, so great and so astonishing that her preservation of her spontaneity was no merit in her. People did not understand her, but neither did she understand them. What did it profit these thousands to lie in wait and watch her dealings with the lady? It would have been far better had no one ever come. Neither the dean nor the prosecutor nor the chief of police would then have troubled her. Love was the important thing, that and the loveliest of beings and nothing else at all. In the very depths of her being Bernadette had not the faintest need of convincing anyone that the lady was real and no figment.

And this passage in Chapter 30 leaves no question about her devotional transcendence:

The public conflict which she herself had instigated was regarded by Bernadette with complete apathy. It would be an exaggeration to say that she was indifferent to it; for her it simply had no existence.6

The antidote for emotional exhaustion

I started this series of posts with a few questions about whether calm, deep feelings—inpletion and devotion, really—have a place in fiction. I believe they do, which is why I have the word “devotional” in this newsletter’s tagline, “A quest for spiritual, devotional, and mystical realism in fiction.” The word is there because without devotion, even the spiritual and mystical parts can get mired in emotionalism if not also intellectuality and materialism.

I’ve suggested, too, that inpletion and devotion can help writers and artists in general avoid the emotional exhaustion (and trauma) that’s considered by many to be part and parcel of the creative process. I hope I’ve demonstrated the simple reason: they allow grace to lift one above emotions altogether, above the plane of agitated feelings as well as above the ego to which those agitations—and any of their destructive effects—cling.

So, just as writers often need to undergo emotional intensity during their creative processes—more than readers will know—writing stories that involve devotional and mystical realism means that authors can also be deeply blessed with inpletional intensity. That’s again why, when I wrote the lashing scene for my shepherdess Ba, I balanced her pain with a deeper, inpletional/devotional experience, for myself as much as for readers. That’s really what I’m aspiring to do through fiction: understand how to employ inpletion to draw readers to that still center between emotional extremes along with the devotional uplift to help readers connect to a greater reality.

For, in the end, I believe that the ultimate purpose of story is not merely to evoke emotion but to rather support the very purpose of life itself: to know God.

I fully recognize that many people, unaccustomed to stillness, quietude, and deep feeling, intentionally seek intense emotional experiences (both positive and negative) because heightened emotions help one to feel alive and awake, which is to say, conscious. Fiction writers and screenwriters purposely evoke emotion because, well, it’s a sure-fire formula for commercial success across all genres! It’s why I think a genre like horror even exists at all: it works with the emotional extremes of fear and terror, which some people prefer over the emotional vibration of, say, romances and thrillers. There is even a sub-genre of erotic romance fiction that’s focused on BDSM practices wherein intense pain is used as a means to intensify sensual pleasure. To each his own, I guess. After all, such intense, outward-directed sensuality doubtless stimulates a kind of heightened awareness. It’s an outward awareness, however, that ultimately separates one from the inner awareness of one’s spiritual reality, one’s true self, and as such can end only in satiety, anguishing monotony, and disgust.

Without going into a longer explanation, I think of this attunement as using one’s free will to actively and deliberately choose or reach up to God and God’s grace as opposed to choosing or reaching out to other options, e.g. material satisfactions. It’s like choosing to subscribe to specific YouTube channels out of the millions that are available.

From the plot summary on https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Last_Battle.

Quoted from https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/resources/reflections-june-2021/

I want to distinguish such devotional prayer and meditation, the purpose of which is to seek and commune with God, which is to say, open oneself to grace, from using prayer and meditation to instead bolster one’s ego and/or achieve worldly success. These latter forms are not devotional and easily become thinly veiled forms of materialism. True spiritual practices and true spiritual experiences loosen the grip of ego upon one’s consciousness. Practices that reinforce the ego should never be called “spiritual” because they altogether omit the Spirit!

I want to distinguish devotional approaches, too, from various forms of therapy, that, although they can certainly help a person balance themselves amidst emotional turmoil, ultimately have limited efficacy because they don’t achieve the uplift of devotion.

It’s passages like these that I think draw me to re-read The Song of Bernadette every year or two (I’ve just finished reading it for the 11th time!), for it is the kind of devotion to which I personally aspire.

I'm learning so much from these.