Inspiring the self-server to self-sacrificer transition in fiction, part 1

Moral health, discontents of the self-server pattern, and the related tragic and redemptive character arcs

(If you like this post, selecting the ❤️ to bless the Algorithm Angels.)

Transition points in seeking God identified three aspects of inspiring or motivating readers toward that ultimate goal: develop a greater clarity about a higher purpose of life than the pattern they’re presently living in, proposing or visualizing ideas about what living with that clarity might look like, and helping to awakening the necessary will and courage to carry out the necessary choices in their own lives.

We’ve already looked at the transition between the first two patterns in Inspiring the transition from self-comforter to self-server part 1 and part 2, so we’re now ready to look at the upwards transition from self-server to self-sacrificer. We also need to look at the potential for a self-server to fall downwards to the self-comforter pattern. This present series, then, has three parts. Here in part 1 we’ll look at the discontents of the self-server pattern along with tragic and redemptive character arcs for that pattern. Part 2 then looks at specific examples of the upward, heroic arc, followed in part 3 with a comparison between “show” morality and authentic morality.

Note that this present series doesn’t spend any time on stories that revel in the self-server pattern without seeking to inspire or degrade, meaning stories that simply praise self-server protagonists for being successful self-servers, which means they deliver only emotional or confirmational inspiration (see The nature of inspiration, part 1). A great deal of modern fiction that’s targeted to self-servers is of this sort, and because it doesn’t serve to inspire readers to seek God in any way, it’s not of particular interest to us here.

Psychological vs. moral health

The transition from self-comforter to self-server, as we’ve seen, is one of cultivating self-interest and personal responsibility, rather than playing the victim. Our culture recognizes this transition as a “step up” both materially and psychologically. We celebrate the bum or the criminal who becomes a “contributing member” of society rather than a leech, who chooses to use his or her time for relatively constructive rather than destructive activities, for making money creatively instead of panhandling or stealing it, and generally for participating in the light of the cultural mainstream instead of living in its shadows.

That’s the main reason that I have “Psychological” as the primary theme of the self-server level, because the difference between that and the self-comforter level is often one of mental health. Being able to rise within the self-server level toward that of the self-sacrificer, too, is a matter of psychological or mental health, which then find expression in other forms of health and success. I think that’s why a great deal of modern fiction is psychological in nature: many readers and writers alike are grappling with psychological issues that can both lead them higher or drag them lower.

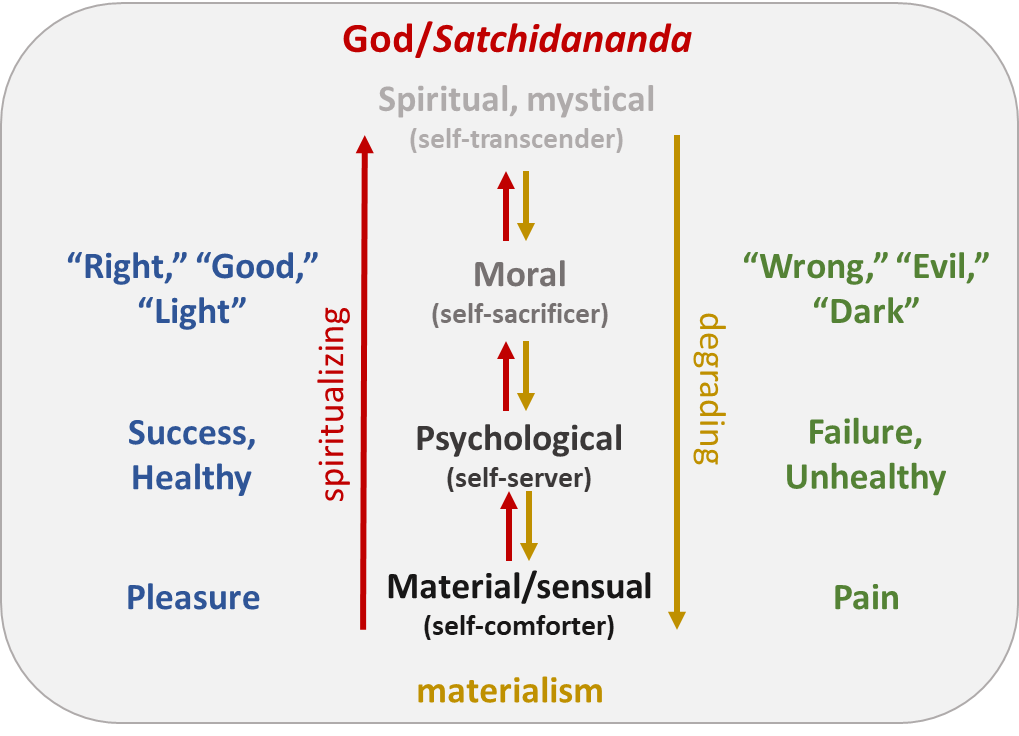

The next step up, though, is not just psychological health but moral health or, simply, morality. From the standpoint of directional spirituality, “moral” behavior is that which raises one toward God/Satchidananda, which for the self-server means rising toward the level of the self-sacrificer (as it also would for a self-comforter). “Amoral” behavior, then, tends to pull one toward the lower end of the self-server pattern, which risks dropping further.

Moral commandments and religious proscriptions are generally meant to prevent people from falling to a lower level by threatening them with terrible consequences. The problem, though, is that those proscription often don’t invite people to rise to a higher level through the attractive power of a higher fulfillment.

Let me put it this way: what is the “self” in the term “self-sacrificer”? It can mean many things, but the deepest meaning is self-interest and ego. A self-sacrificer, then, seeks to overcome narrow self-interest and ego-motivation through an expansion of sympathy and self-identity. Within that self-expansion, moral proscriptions become increasingly unnecessary: you don’t need a law or commandment to prevent stealing from others because you understand and even feel the pain it would cause others. You don’t need rules to force honesty: you choose to be honest because you’ve realized that the inner joy of honesty is far more valuable than whatever material gains you might accrue with dishonesty.

Here’s an example that you might not even consider dishonest. Suppose you just finished buying groceries and are about to drive off. You look at your receipt and you notice that the cashier missed a $3 item. What do you do? Do you rejoice in your “luck” or “good fortune” or “grace” or whatever you want to call it and just go your way? Or do you consider how the oversight might hurt the store (and possibly the cashier) and thus take the time to deliberately go back inside to pay for that item? And what if it was a $50 item? What if you didn’t realize the oversight until you got home? Would you go out of your way to correct the mistake by making the drive back to the store?

And how would you feel when making such a deliberate act of honesty, even at material cost to yourself, versus living with the realization that you could have chosen to correct the mistake, but didn’t?

A self-server wouldn’t feel any remorse about just accepting the “good” fortune. But the self-sacrificer feels an even greater joy in making the personal sacrifice for the sake of truth, even though and perhaps especially when nobody expects that sacrifice.

This is what I mean by “right” and “wrong” in the diagram—not laws or proscriptions, but an innate sense of truth and goodness that needs no laws. That’s the moral compass of a self-sacrificer.

Making money “creatively” vs. morally

In the first paragraph of the previous section, I almost put the word “creatively” in quotes where money-making is concerned because although many self-servers pursue their goals honestly and sincerely, which is to say, morally, there are plenty of examples of self-servers using morally reprehensible ways to make money.

Think of all the creative schemes that con men and hackers use to scam the vulnerable and the desperate. Think, too, of those who are perfectly willing to exploit existing laws through which they avoid paying any taxes whatsoever while continuing to enjoy tax-funded benefits, which is really a form of theft.1 Or consider the professional gambler nicknamed “The Joker” who in early 2025 won $57 million by legally exploiting flaws in the design of the Texas lottery. The Texas governor called it “the biggest theft from the people of Texas” in the state’s history.2

Such outrage, even when no laws are broken and no regulations are violated, demonstrate the difference between doing what’s possible and doing what’s “right.” Morality is that sense of “won’t” even when you can—and even without external consequences—because you know there are inner consequences to consider and value peace of mind paramount. The consideration of those inner consequences is what draws one toward the self-sacrificer pattern.3

Earning money doesn’t make one a self-server

Let’s be clear, too, that earning money and taking care of oneself do not, in and of themselves, ensconce one in the self-server pattern any more than having sense experiences and occasionally seeking comfort makes one a self-comforter (see Self-comforter to self-server, part 1). Nor is having or earning money a non-spiritual activity. The great mystic Paramhansa Yogananda said that “Earning money honestly and industriously to serve God’s work is the second greatest art to the art of realizing God.” In fact, his most advanced disciple, James J. Lynn, was a self-made millionaire businessman.

In cultures that lack social institutions that directly support people who give their lives to service (self-sacrficers) or to seeking God (self-transcenders), it’s necessary for those who feel so called to find honest ways to support themselves. Outwardly, then, they may not appear any different than an honest self-server who sees earning money and gaining possessions as the very purpose of existence or integral to one’s self-identity. Inwardly, however, both the self-sacrificer and the self-transcender think of earning money merely as a means to their respective life goals rather than a goal in itself and readily set it aside when it’s no longer necessary.

Discontents of the self-server pattern

One of the distinctions between a self-server and the self-comforter is that the self-server has realized that a greater fulfillment can be found with the application of creative self-effort than simply waiting for fortune to smile on you (somehow).

In time, however, living in this pattern reveals an underlying monotony. The same “diminishing marginal utility” noted with the self-comforter in Self-comforter to self-server, part 1 applies equally here: the same amount of effort doesn’t necessarily produce the same fulfillment. Furthermore, in a similar cruel irony, it’s quite easy to cultivate more desires than you’re able to satisfy. No matter how much money they earn or accumulate, most people believe they won’t be happy until they have just a little more.

That “little more” becomes a never-ending quest: just look at how many people become wealthy and powerful and own everything they could dream of and yet are miserable because they remain emotionally, morally, and spiritually impoverished: God/Satchidananda (see Everyone is seeking God but most don’t know it), or even just a little peace of mind, continues to elude them.

When dissatisfaction sets in, there are three paths to take. The upward path, which is what we’re talking about in this series, is to relinquish the quest for merely personal gain and begin to consider others’ well-being along with your own. We’ll talk more of that in part 2.

A second path is to give up and seek escape by descending into the self-comforter pattern. For a time, it seems a relief if only because it’s different. And if a self-server has some savings to live on in the meantime, they can indulge themselves with little apparent risk. Indeed, that’s how many people envision retirement, with the perhaps unspoken hope that they’ll die naturally before their funds dry up. In any case, those who descend into the self-comforter pattern will inevitably run into its discomforts all over again.

The third path is to resort more and more creatively desperate or risky measures, often stretching the limits of laws both social and moral. Where the self-comforter seeks to intensify their sense-experiences, self-servers generally seek an expansion of power. But even here, greater power only delays the inevitable: just think of how those who rise or have risen to the very pinnacles of political power, such as Stalin, still fail to find lasting fulfillment.

Tragic and redemptive character arcs

Struggles with the discontents of the self-server pattern are frequent themes in literature, film, and stage plays, such as The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Bonfire of the Vanities by Tom Wolfe, Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, and Shakespeare’s MacBeth. In the latter, although MacBeth has attained the kingship and all the power he ever sought, he still finds no satisfaction. He laments this in his soliloquy of Act 5 Scene 5 after he learns that Lady MacBeth is dead (likely by suicide brought about by her own madness in pursuit of power):

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.4

You can watch the segment with that passage here:

MacBeth clearly follows a tragic story arc—the full title of the play is, after all, The Tragedy of MacBeth. As noted at the end of Self-comforter to self-server, part 2, a tragic arc warns readers about the consequences of the protagonist’s choices, thereby inspiring readers to make different choices themselves (motivational inspiration). Tragedies like MacBeth in which the protagonist falls and remains fallen are thus directed at people in the self-server pattern who might be tempted to seek wealth and power for their own sake.

Another frequent theme to which the same readers can relate is redemption, a heroic character arc that begins with a fall that is then followed by some degree of recovery. In our present context, the heroic arc concerns a protagonist in the self-server pattern who tries to escape into the self-comforter pattern but experiences its pains all over again. They then realize what they’ve lost and strive to pick themselves up again.5

An important point here is that characters who follow a redemption arc are not, by default, self-comforters: it’s only a temporary state. Stories can depict that fall directly, of course, or they can start with a protagonist who has already fallen. Either way, readers understand that the fallen self-server protagonist is seeking redemption, which can help readers in that pattern appreciate what they have before taking a fall themselves.

As heroic as redemption stories are, merely having a character fall and then recover to their previous status doesn’t actually serve to inspire readers in the self-server patten to transition higher to the self-sacrificer pattern. These stories can, of course, inspire or motivate self-comforters upwards, but for readers in the self-server pattern they provide only the same kind of warning as tragedies.

For this reason, something more is still needed to inspire the transition to the self-sacrificer pattern, which we’ll pick up in part 2. Until then, do share your thoughts.

(Continued in part 2)

(If you like this post, selecting the ❤️ to bless the Algorithm Angels.)

And one that its perpetrators try to morally justify by claiming that taxes are “evil.”

See How a Secretive Gambler Called ‘The Joker’ Took Down the Texas Lottery (Wall Street Journal) or The two men behind the scheme that won a $57 million Texas lottery jackpot (Texas Standard).

Another recent example is Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg saying that AI “friends” can basically substitute for human beings. The self-serving hypocrisy here, which is not lost on many commentators, is that Zuckerberg is basically proposing that AI products from Meta can help solve problems like loneliness that Meta’s social media offerings like Facebook and Instagram helped to exacerbate. But one does not expect people like Zuckerberg to uphold any kind of moral vigor.

Self-sacrificers and self-transcenders can also fall from their patterns into any of the lower ones and then follow a redemption arc. In this post, however, we’re focusing solely on the transitions that begins with the self-server pattern.