Inspiring the transition from self-sacrificer to self-transcender in fiction, Part 1

Opening oneself as a channel for God's grace rather than driving personal agendas

(If you like this post, selecting the ❤️ to bless the Algorithm Angels.)

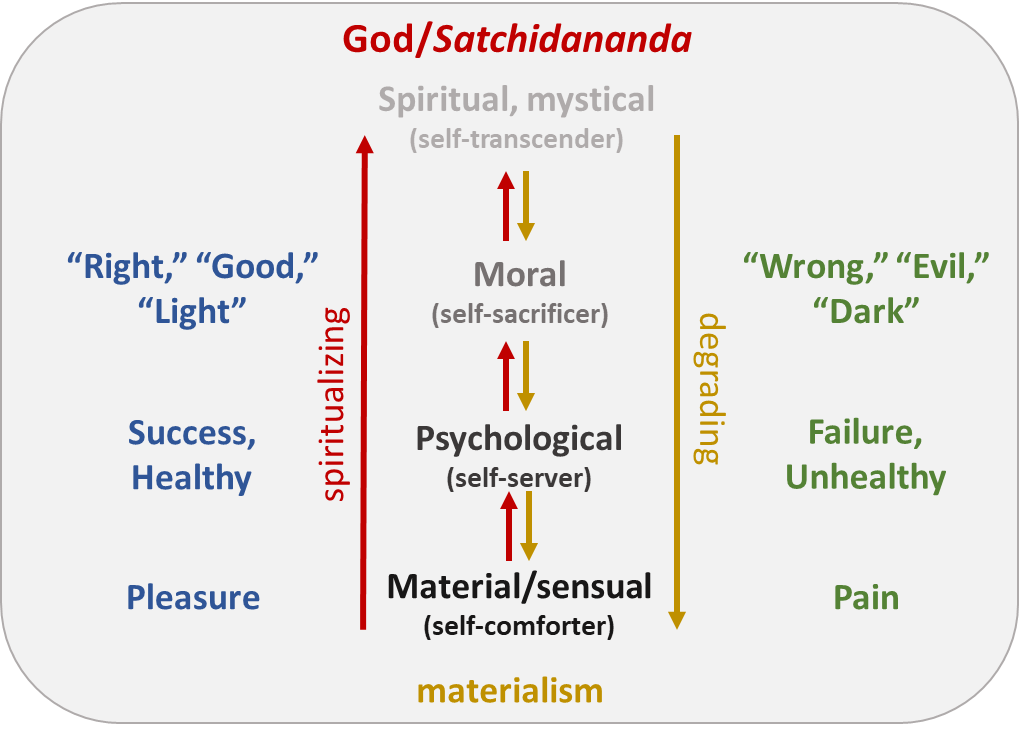

In this extended series of posts on Transition points in seeking God, which we started a while back with the post Everyone is seeking God but most don’t know it, we’ve been asking the question, “What does it mean to inspire someone to seek God?” which is to say, “What does it mean to inspire someone upwards toward a deeper experience of what everyone truly wants, which is the ever-existing, ever-conscious, ever-new joy of God that is succinctly captured in the Sanskrit term, Satchidananda?”

As we’ve seen, such inspiration depends on the particular behavioral pattern under consideration, especially when people in those patterns may not be ready to think about seeking God in those terms. Thus, the transition from the self-comforter pattern to that of the self-server is marked by greater energy and a greater self-interest (health, wealth, responsibility, etc.) that enables one to climb out of the pits of self-indulgence and integrate with the mainstream of society. Similarly, the transition from self-server to self-sacrificer is marked by a greater sense of moral rightness that comes with an expanded sense of self and self-interest, even if doing so demands a sacrifice of personal comforts, conveniences, and freedoms.

One is naturally compelled to make these upward transitions—away from materialism/sensuality and toward God—because trying to find the permanent, ever-new joy of Satchidananda that we all crave is simply not possible with any lesser fulfillments. Discontent, bitterness, and anger set in and even consume up until we finally admit that we need to try a different approach.

The same is true for people in the self-sacrificer pattern. Although this pattern is comparatively higher and more fulfilling than those of the self-comforter and self-server, along with being morally and socially praiseworthy, it’s inevitable that self-sacrificers, no matter how hard they work or how many personal sacrifices they make for whatever causes they serve, will feel that’s something is still missing. Something is still needed to make the transition to the level of the self-transcender wherein that permanent fulfillment can finally be realized.

The final sacrifice is the sense of self itself

What is that missing piece? At first glance, we might think (and perhaps often say) that the answer is just “God,” especially because God/Satchidananda lies at the top of the transitions diagram we’ve been using this whole time. To some extent this answer is correct, because there are many people operating within the self-sacrificer pattern who push away anything to do with God, religion, and genuine spirituality and thus limit their effectiveness.

But it’s actually not enough to simply say “God is what’s missing” because there are many people who do sincerely believe in God, and who have even had direct experience of God’s reality to put all doubt to rest, yet who are operating within the self-comforter, self-server, and self-sacrificer patterns. Having a relationship with God, in other words, doesn’t automatically make one a self-transcender: it greatly depends on the nature of that relationship.

We’ll explore the spectrum of relating to God in a future post, but for now, the crux of the matter is this: is the relationship based on wanting to use God for our own purposes, or is it based on asking—and allowing—God to use us for his purposes?

This question is challenging and demanding. Many religiously-minded people claim that they’re doing “God’s will” when they’re really just enlisting God’s authority in support of one’s own agenda. Terrorists of any fundamentalist persuasion excel at this delusion, but I’m thinking more about the self-assertive approach I’ve encountered in many sermons, books, and other presentations wherein the author or speaker frequently cites cherry-picked passages—even just phrases—from the Bible or some other scripture that are often taken out of context, to make their point. There’s nothing quite like bringing in Saint Paul, a prophet, or even Jesus himself to complete your thoughts.

A different and humbler approach is to take a longer passage in toto and then ask, “What is this passage, especially taken within its larger context and in the context of other passages on the subject, really trying to tell us?” An example is the “The Magnificat,” a Christmas sermon delivered by my friend Samantha Rose McRae (also see the video starting at 38:24), in which she reflects on the applicability of Luke 1:39–55 (Mary’s meeting with Elizabeth). Toward the end, Samantha tells of how she’d been repeating Mary’s “Magnificat” song in this passage several times each week while she is studying at seminary. “But,” she writes,

I have often recited it without paying attention to the words I was saying. Using my eyes to graze over the words and repeat them with my lips while my mind was set firmly on something else—generally what I had missed in class readings.

It wasn’t until the first week of Advent that I think it really struck me what Mary was saying. Throughout the Bible, people are always singing when they are met with an occurrence that is praiseworthy. It isn’t just that they are excited or happy, but it is usually at a time that is for something monumental. Life-altering. Or in Mary’s case, world-altering. So, when it came time to pray over this passage, and asking God, “God—what is it you want me to take from this passage? What do you want me to say?”

Truly submitting to God’s will is not easy. It can and often does prove inconvenient, difficult, demanding, and life-altering, and not in the ways we expect. After all, if God wants us to find that everlasting fulfillment in him, why would he (or saints, prophets, and masters speaking on his behalf) simply reinforce our attachments, comforts, prejudices, biases, limited self-image, and narrow-minded opinions?

Here, then, is an essential inflection point in the transition between the self-sacrificer and the self-transcender: the surrender or sacrifice of the very self that identifies with both achieving any kind of effect in the world and with making sacrifices for the sake of that cause.

Self-sacrificers often rejoice in or even brag about how much they have given up or how much suffering they have borne for the cause. Giving up one’s own life for a cause, too, is considered the “ultimate” sacrifice. On the other end of the spectrum, they often rejoice in or brag about all the “good” they’re doing through their work.

Yet in all these cases there still remains an egoism, otherwise known as pride, that keeps one firmly entrenched on the self-sacrificer level and therefore distinctly separate from God. And it’s this prideful separation—ego—that’s exactly what the self-transcender is seeking to overcome in the quest to know or realize God. Ego is truly the final and ultimate sacrifice.

Channels for the flow of God’s grace

Entering the self-transcender pattern doesn’t mean that one has already overcome ego. It simply means that doing so is now one’s driving goal. As stated back in Everyone is seeking God but most don’t know it, the self-transcender says, “The purpose of life is God-realization,” which is to say, to know God to the fullest extent possible.

Cleary, though, for the person who has just transitioned into this pattern, there’s more work to be done. A lot more work. That’s why my description of the self-transcender in that post was “saints, aspiring or actual.”

As an aspiring saint, the self-transcender seeks now to set aside personal agendas and seeks instead to be a channel through which God’s light, love, joy, peace, wisdom, and power—which we can collectively call grace—can flow into the world.

In this way, we can model each of the behavioral patterns as a kind of filtering lens for this grace. God, as great sages have repeatedly said, works in the world through instruments, with human beings the most capable instruments within material creation.1 I think that’s the point of Jesus’ “blessedness” in the Beatitudes (Matthew 5:3–12). And because grace is infinite, meaning both that it’s equally available to everyone and that it cannot be exhausted or diminished no matter how many people draw upon it.

Because every individual soul occupies a unique place in time and space, each one of us forms a particularized intersection between the Infinite and the finite: like a lens, we each bring some portion of the Infinite to a focus within our time-bound material reality.

A perfected human being—a saint, a master, a fully-liberated soul, a Christ, however you want to describe it—is a perfect, flawless lens. Though the individuality of that soul remains, there are no thwarting crosscurrents of ego to obscure or distort the flow of God’s grace, no thoughts of “What I want” that interfere with that flow (that is “God’s will”). This state of flawless purity is, in effect, what it means to truly “know God” or to “realize God.”

Achieving that perfection is again what a self-transcender seeks deliberately. This is why self-transcenders naturally embrace increasing degrees of renunciation, not in the negative sense of suppression but rather as something that arises from the growing awareness—cultivated in silence through prayer, contemplation, and meditation—of how various thoughts, feelings, actions, desires, and attitudes obstruct and distort the flow of grace. The more one cultivates the desire to purify one’s lens, desires for any and all lesser “fulfillments” get absorbed into that upward stream of devotion.

Taking a step down, the lens of the self-sacrificer is darkened somewhat with personal desires, opinions, and especially the thought, “This is the way the things ought to be,” which effectively says, “I know better than God does; I’m wiser and more aware of what’s truly needed.” Many self-sacrificers who consider themselves religious yet nurture this conceit as much as atheists and secular humanists. Even if there’s some attunement to the greater realities of “human community,” there’s still the thought that that community knows better than God.

Either way, the self-sacrificer’s lens obstructs and distorts the flow of grace. Sure, plenty still gets through at this level via “good works” and a generally expansive consciousness that cares about others, but quite a bit of grace does not. Just consider how many otherwise nobly minded self-sacrificers are weighed down by the burdens of their concerns and struggle to find any real joy or peace.

The lens of the self-server is darker still by contracting into the selfish thoughts of “What’s good for me?” and into the narrow confines of self-involvement. Consequently, most of God’s grace is obstructed and what does get through is significantly distorted.

And finally, the lens of the self-comforter becomes so dark with sensualism and deadened awareness that God’s grace is blocked almost entirely and undergoes such distortion as to be well nigh unrecognizable. Only the faintest traces make it through, perceived, perhaps, by only with wisest of souls.2

To inspire self-sarificers to step into the self-transcender pattern is to inspire them to begin taking deliberate steps to clear out personal opinions, attachments, and ideas about how things ought to be in order to become a better channel for God’s grace. Those steps can take many forms, all of which provide ample opportunities for fiction that depicts those choices and thus inspire readers to make the transition for themselves.

We’ll explore these matters in subsequent posts. Until then, your thoughts are welcome.

(If you like this post, selecting the ❤️ to bless the Algorithm Angels.)

Which is to say that non-material angels or other such beings may be more capable instruments because they’re not bound by physicality, but let’s set that detail aside.

Such an enlightened sage is described thus in the Bhagavad Gita: “Unaffected by outward joys and sorrows, or by praise and blame; secure in his divine nature; regarding with equal gaze a clod of mud, a stone, and a bar of gold; impartial toward all experiences, whether pleasant or unpleasant; firm-minded; untouched by either praise or blame; treating everyone alike whether friend or foe; free from the delusion that, in anything he does, he is the doer: Such a one has transcended Nature’s triune qualities.” (XIV:24-25)