The fictional character I would most like to be, part 2

Implications of the title of “A Christmas Carol” and how Dickens describes the Scrooge’s true character

(If you like this post, bless the Algorithm Angels, the Digital Devas, or whatever you’d like to call them by selecting the “heart” icon ❤️ even if you’re not a subscriber. It helps!)

In Part 1, I endeavored to demonstrate that Ebenezer Scrooge in Charles Dickens’ classic story, A Christmas Carol, is not what he seems to be. The very fact that he’s granted the grace of a chance to redeem himself indicates that his outer callousness is nothing more than a mask behind which he’s hiding a more fundamental nature.

In this post, we’ll look at two more factors that demonstrate how Scrooge becomes not just a nice person, but a saint…if not more.

(Note to subscribers: I won’t be posting anything for Dec 28th and Jan 4th to take a break over the holy-days. The next post will be on Jan 11th.)

What’s in the title, “A Christmas Carol”?

Because A Christmas Carol is such a perennial holiday favorite, I think we just take the title for granted. But why did Dickens call it A Christmas Carol and not just A Christmas Story?

Let me ask this question: what, exactly, is a “Christmas carol”? You answer probably names many favorite songs like Silent Night, The First Noel, O Little Town of Bethlehem, and so on. In modern times the list might also include secular pieces like Jingle Bells and Frosty the Snowman. Is a “Christmas carol” then simply a song about Christmastime and wintery experiences?

Not really. The original idea of a Christmas carol means a song (or perhaps a story, given that many of these songs are stories) specifically about the coming of Christ.

Let me repeat that: a Christmas carol is a song or story about the coming of Christ.

And yet in this story bearing that title, Dickens never once mentions Christ or Jesus. Is that fact not odd?

It would be except for the fact that the story is indeed about the coming of Christ: it is about the awakening of “the Christ” within Scrooge himself.

I’ve already argued in Part 1 that the gruff Scrooge we first meet in the story is merely a mask, that Scrooge’s authentic self is joyful, loving, caring, and compassionate. To further that point, reflect on how Dickens, in Stave Two, repeatedly characterizes the Ghost of Christmas Past as light:1

…from the crown of its head there sprung a bright clear jet of light, by which all this was visible; and which was doubtless the occasion of its using, in its duller moments, a great extinguisher for a cap, which it now held under its arm. (33)2

Furthermore, Marley in Stave One speaks briefly of the light of “that blessed Star which led the Wise Men to a poor adobe,” (27) a clear allusion the Light of Christ as the Bible describes in John 1:4 and John 1:9.3 In this way, the Ghost of Christmas Past represents that Light of Christ that dwells within each soul (the light that is “the light of men” as St. John puts it), the very Light that Scrooge has suppressed all these years beneath his mask. Dickens, in fact, pretty much says this through Scrooge’s first reaction to the celestial visitor:

Perhaps, Scrooge could not have told anybody why, if anybody could have asked him; but he had a special desire to see the Spirit in his cap; and begged him to be covered.

“What!” exclaimed the Ghost, “would you so soon put out, with worldly hands, the light I give? Is it not enough that you are one of those whose passions made this cap, and force me through whole trains of years to wear it low upon my brow?” (34)

The Ghost, too, specifically says that the “Past” that is part of his title is specifically Scrooge’s past, which is to say that Scrooge’s past is full of light.

Scrooge’s experiences with this Ghost in Stave Two, as mentioned in Part 1, are all about reawakening this truth of his own being, the Light of the Indwelling Christ that at one point, as indicated by the Ghost’s appearance after Scrooge witnesses the Christmas party at Fezziwig’s: “the light upon its head burnt very clear.” (47)

Scrooge has long tried to suppress that Light, but finds, at the end of Stave Two, that it’s no longer possible:

He turned upon the Ghost, and seeing that it looked upon him with a face, in which in some strange way there were fragments of all the faces it had shown him [that is, all the love he’d buried], wrestled with it.

“Leave me! Take me back. Haunt me no longer!”

In the struggle, if that can be called a struggle in which the Ghost with no visible resistance on its own part was undisturbed by any effort of its adversary, Scrooge observed that its light was burning high and bright; and dimly connecting that with its influence over him, he seized the extinguisher-cap, and by a sudden action pressed it down upon its head.

The Spirit dropped beneath it, so that the extinguisher covered its whole form; but though Scrooge pressed it down with all his force, he could not hide the light, which streamed from under it, in an unbroken flood upon the ground. (50-51)

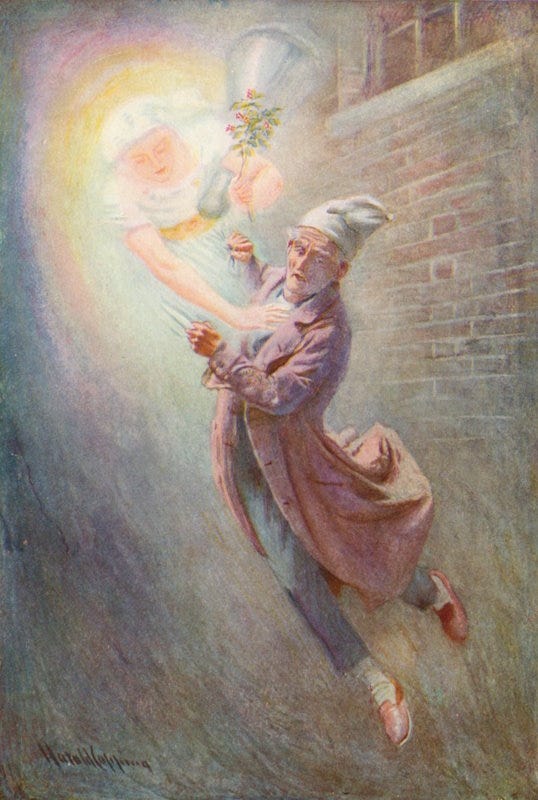

Read that last phrase again: but though Scrooge pressed it down with all his force, he could not hide the light—for the indwelling Christ, the inner Light of love, charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence (to use Marley’s words from Stave One), is reasserting itself and can no longer be hidden, as nicely rendered in the 1999 movie with Patrick Stewart shown in the still shot and video clip below.

Dickens, then, may have just as well entitled his story, A Coming of Christ, for here, on Christmas Eve, the Christ is about to be born anew.

What Scrooge reveals himself to be: far more than a nice guy

At the end of Stave Four, Scrooge’s final words to the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is a certain vow:

“I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach.” (97)

And, as illustrated in Stave Five, we can say that on one level, Scrooge’s reawakening is simply to what we might call the “spirit of Christmas”—seasonally appropriate cheer and generosity and all that. As Dickens writes:

…and it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge. (106)4

And with his final lines, Dickens invites the reader to do the same:

May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God bless Us, Every One! (106)

For most of us reading A Christmas Carol, this message is sufficient and satisfying.

And yet just as with the story’s title, Dickens also offers a much deeper possibility if we’ve “ears to hear,” as Jesus put it.

For one, reread the quotes above but change “I will honour Christmas” to “I will honour Christ.” Again, Dickens doesn’t mention Christ or Jesus anywhere in the story, but I think we can often read “Christmas” as “Christ,” which dramatically changes the implications of Scrooge’s vow.

Look also at the words the second to last paragraph:

Scrooge was better than his word. He did it all, and infinitely more…He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world. (105)

Let me rephrase what Dickens is saying here: Scrooge became as good as anyone, anywhere in the world, past or present. Such a statement puts Scrooge in some pretty illustrious company, does it not? For it must necessarily rank him among all those who so fully demonstrated what it means to be truly human: the saints. That’s why, in Part 1, I called Scrooge a saint. Saint Ebenezer Scrooge.

But I also think Dickens is raising, as he puts it in the frontispiece of the book, “a Ghost of an Idea” that may “haunt [readers] houses pleasantly”: the idea that Scrooge becomes something even greater. For to say that he became as good a man and master as anyone in the world is a comparison that must necessarily include a certain Galilean Master who, about 1800 years before Dickens penned his story, was known in towns and cities like Bethany, Capernaum, Jerusalem, and Bethlehem, the same Star about whom we sing in all those other Christmas carols.

In other words, this passage indicates that Scrooge becomes not just a saint in general terms, but a fully Christlike saint. And Dickens even slips in another word that modern minds might dismiss as mere hyperbole: the infinitely in “He did it all, and infinitely more.” What if Dickens meant it seriously, that the Scrooge who has become as good as Jesus himself has even fulfilled the promise of John 1 verses 9 and 12, which speaks of the effect of receiving the Light of Christ, which is to also say, opening oneself to the Light of Christ?

That was the true Light, which lighteth every man, that cometh into the world.

[To] as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God…. (KJV)

I read Dickens as thus saying that Scrooge becomes not just a Christlike saint, but a “Christ,” which, in its titular form, means one “Anointed by God” with the omnipresent (“only begotten”) Christ Consciousness. That consciousness is that state of mystical oneness with God that I wrote about in Three literary accounts of mystical union, part 2. It’s that state from which the medieval German mystic, Meister Eckhart, could say, “I move my hand, and Christ moves, who is my hand.” It’s the state in which one is able to say, like Jesus, “I and my (Infinite, Omnipresent, Omnipotent) Father are one.” As Meister Eckhart also said (Sermon 66), “Between the only begotten son and the soul there is no distinction.”5

That oneness is exactly what I aspire to myself, which is why a saint, Saint Ebenezer Scrooge, indeed sits atop my list of fictional characters that I would most like to be.

In closing

A Christmas Carol, then, is a story about the coming of the Christ, the awakening of the Indwelling Christ, the Infinite Christ Consciousness, within the soul of Ebenezer Scrooge, a soul who, at the outset, we’re led to believe is lost. And yet he is redeemable and redeemed, and then some, which is, I believe, what Dickens holds as possible for each of us through the words of Tiny Tim: “God Bless Us, Every One!”

All we need do is drop our own masks of ignorance, want, and self-involvement to which we cling, thereby revealing, as with Scrooge, the inner beauty and joy and love of the Christ within.

A Blessed Christmas and New Year to you.

(If you like this post, bless the Algorithm Angels, the Digital Devas, or whatever you’d like to call them by selecting the “heart” icon ❤️ even if you’re not a subscriber. It helps!)

He also depicts the Ghost on page 34 in such a way as to suggest that it may be a seraphim or even an archangel, as when it appears to have twenty legs or appears as only a disembodied head, which evokes something of how Old Testament prophets like Ezekiel try to describe such heavenly creatures, as in chapters 1 and 10.

“Extinguisher” in Dickens’ time is what we’d call a candle snuffer, as what we today call a fire extinguisher had not yet been invented.

“In him was life; and the life was the light of men.” John 1:4, KJV. “That was the true Light, which lighteth every man that cometh into the world.” John 1:9, KJV

Dickens makes a pun at the beginning of the paragraph: “He had no further intercourse with the Spirits, but lived upon the Total Abstinence Principle, ever afterwards.” (106) Abstinence, of course, is the abstinence from alcoholic drinks, otherwise known as “spirits.”

Is it blasphemous to suggest that the Christ state can be expressed through more than one being? Jesus himself says in John 14:12 (KJV): “Verily, verily, I say unto you, He that believeth on me, the works that I do shall he do also; and greater works than these shall he do; because I go unto my Father.” To “believe” in Christ in this sense is to be an open channel for divine energy. In Luke 6:40, to, Jesus says, “The disciple is not above his master: but every one that is perfect shall be as his master.” And, “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect” (Matthew 5:48).