Christmas is drawing near, so I wanted to share an essay that, as you’ll soon see, is closely related to a favorite Christmas classic.

And if you like this post, bless the Algorithm Angels, the Digital Devas, or whatever you’d like to call them by selecting the “heart” icon ❤️ even if you’re not a subscriber. It helps!

“What fictional character would you most like to be?” This question provokes great entertainment in literary circles. People will likely name any number of the most loved and virtuous heroes and heroines of our heritage. Some choose the likes of Elizabeth Bennet (Pride and Prejudice), Atticus Finch (To Kill a Mockingbird), or Gandalf (Lord of the Rings). Others might identify as their model character Charlie Bucket (Charlie and the Chocolate Factory), or perhaps Hermione Grainger, Jane Eyre, Katniss Everdeen, and others who rank among such distinguished company.

My own short list includes, as honorable mentions, Samwise Gamgee in Lord of the Rings, for his loyalty, courage, and hopefulness, and Luna Lovegood in Harry Potter for her centeredness, intuition, and openness to and ability to accept the extraordinary.

The bronze medal on my list goes to Marcellus Gallio in Lloyd Douglas’ The Robe for his sincerity and complete self-offering. According to the timeline in that story, Marcellus, a Roman Tribune, becomes history’s second Christian martyr after Stephanos (Stephen), of whose stoning Marcellus is witness. It is Stephen’s death, during which he sees Christ coming to him, that puts the final touch on Marcellus’ acceptance of the nascent faith. Were he an actual historical personage, Marcellus would certainly have been canonized a saint.

My silver medalist is another saint, Bernadette Soubirous, as depicted in Franz Werfel’s The Song of Bernadette, for her purity of devotion and utter surrender to the Lady. I find both qualities deeply inspiring.

Given Marcellus and Bernadette, you are probably already expecting that another fictional saint tops my list. Perhaps various candidates are already coming to mind.

But my top choice will likely surprise you, because it’s not a character that you’re likely to find on others’ lists of inspiring literary favorites.

The fictional character I would most like to be is…drum roll please…

Ebenezer Scrooge.

Yes, that Scrooge. That nasty piece-of-work protagonist of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

Wow. I can feel your visceral disgust and repulsion even as I write my first draft of this essay, long before you're even reading it. I may as well have named any number of other despicable figures in English literature, such as Gollum or Wormtongue (Lord of the Rings), Dolores Umbridge or Bellatrix LeStrange (Harry Potter), Augustus Gloop (Charlie and the Chocolate Factory), Captain Ahab (Moby Dick), Lady MacBeth (MacBeth), Iago (Othello), or, to throw in everyone's favorite historical scapegoat, Judas Iscariot.

But seriously, I am being completely honest: I really would like to be Scrooge. And I'm not saying this for shock value, as I might be if I said something like, “I once drank out of a toilet.” Nor am I simply trying to do something unexpected, even though I am the type of person who, when asked to sort themselves into different corners of a room during a personality workshop, will roguishly stand in the middle, refusing to be pigeonholed and rashly asserting uniqueness by breaking conventional patterns. I’m just telling the truth.

I understand your reaction, of course.1 In the English lexicon, Scrooge has become virtually synonymous with meanness, selfishness, and “Bah! Humbug!” cynicism. A stingy miser. A heartless tightwad. Scoundrel. Killjoy. “Don't be a Scrooge,” people say. “You're such a Scrooge!” they mock, summoning the image to point out dour, self-serving behaviors. Scrooge, in short, is a type of person that most people wish to avoid in every way, let alone emulate. (That this is the common image of Scrooge is demonstrated by the kind of images that AI generates for the prompt, “Ebenezer Scrooge,” an example of which is below.)

But take a breath, let the dust of your disbelief settle a bit, and let me explain my choice. For I’m not interested in what I argue is but a temporary Scrooge, I’m interested in who Dickens reveals him to truly be.

Which Scrooge am I talking about?

The aforementioned qualities describe only the Scrooge presented in the opening scenes of A Christmas Carol, the Scrooge that humbugs his nephew, the Scrooge that talks nonchalantly about “surplus population,” the Scrooge that chases away singing children, and the Scrooge that demands an exact accounting of every measly chunk of coal.

Yet Scrooge doesn’t stay that way. Unless your exposure to English literature is limited to SpongeBob SquarePants and Marvel Comics, you’re fully aware that Scrooge is radically different by the end of the story. It’s an odd dichotomy: Scrooge is virtually synonymous with “despicable,” it’s true, and yet his story is often cited as the classic example of a transformational character arc, “the greatest character-change story ever written” according to the bestselling author, James Scott Bell (Write Great Fiction - Plot & Structure, page 142). For by the end of the book, Scrooge has become not only kind and generous, but also, as I’ll explain in this two-part post, a saint—and even more than a saint.

And that’s why I give him top spot on my list.

Now, there’s so much I could say on this topic, and so much supporting evidence throughout A Christmas Carol, that a full essay could probably serve as a Masters’ thesis. For the sake of brevity, then, I’m going to focus on just three key factors.

The first, which is the subject of the remainder of Part 1 here, is the fact that Bob Marley, whose ghost appears in Stave (Chapter) One, has somehow procured “a chance and hope of escaping my fate.” It really begs the question: Why does Scrooge, this epitome of cynicism and meanness, merit a second chance in the first place?

Part 2 then picks up the two other factors: Dickens’ chosen title, A Christmas Carol, and the simple but profound comparatives that Dickens uses to describe Scrooge at the end of the story. Both of these details are, to my mind, quite revealing.

Graced with a chance of escape

When most people think of A Christmas Carol, and especially if they’ve watched any number of modern retellings, they probably think that Scrooge surrenders his hard heart only after being dragged unwillingly through all the experiences with the three Ghosts, which culminate in the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come forcing Scrooge to face his mortality.2

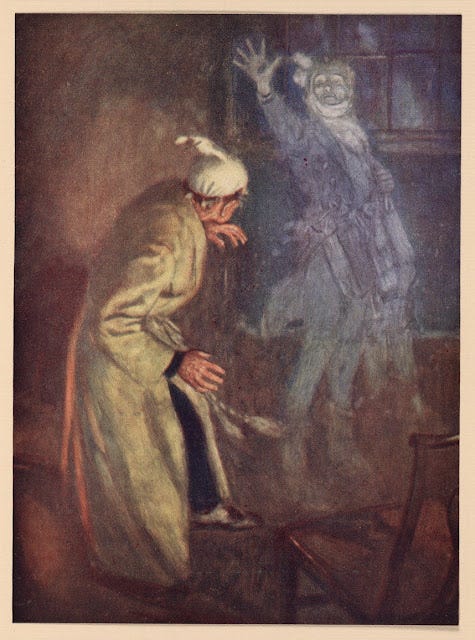

In Dickens’ original, however, the mean-spirited Scrooge that dominates our collective understanding doesn’t even make it out of Stave One. Instead, a deeper and more authentic nature begins to emerge almost as soon as Marley’s ghost appears and well before the entrance of the other Christmas Spirits. And that true self shows itself throughout Scrooge’s encounters with those Spirits.

Barely a fifth of the way into the book, and just after Scrooge initially mocks Marley with a what turns out to be the final “Humbug” of his life, we read this passage (italics added for emphasis):

At this the spirit [Marley] raised a frightful cry, and shook its chains with such a dismal and appalling noise, that Scrooge held on right to his chair, to save himself from falling into a swoon. But how much greater was his horror, when the phantom taking off the bandage around its head, as if it were too warm to wear indoors, its lower jaw dropped down upon its breast!

Scrooge fell upon his knees, and clasped his hands before his face.

“Mercy!” he said. “Dreadful apparition, why do you trouble me?” (24-253)

How is it that Scrooge, whom we’re given to understand as a veritable fortress of self-assurance, suddenly swoons, is horror-stricken, and drops to the floor begging for mercy? Why doesn’t he just dismiss it all as humbug? How has Marley's singular wail broken Scrooge's pride with the same swift efficacy as Alexander slicing through the Gordian knot?

Perhaps Scrooge isn’t the man we thought he is, or even the man he thinks himself to be.

Consider, too, how Marley describes Scrooge’s karmic burden (his debt of sin, that is) as more “ponderous” than “the chain I forged in life,” but then says:

“…you have yet a chance and hope of escaping my fate. A chance and hope of my procuring, Ebenezer.” (28)

How is it that Scrooge merits a second chance not afforded to Marley, but one that Marley is yet able to procure?

I think the answer is that Scrooge’s callousness is but a mask, behind which the real Scrooge is hiding. Marley’s despairing cry strikes the first crack in that mask, and his experiences throughout the story continue to shatter it.

One example may suffice. Toward the end of Stave Two, the Ghost of Christmas Past forces him to witness his breakup with Belle, his betrothed (46). If Scrooge was truly hard-hearted, he’d watch this scene (and others) without remorse, perhaps even laughing derisively as he justifies his actions all over again. Instead, Dickens shows him in deep pain:

“Spirit!” said Scrooge, “show me no more! Conduct me home. Why do you delight to torture me?”

“One shadow more!” exclaimed the Ghost.

“No more!” cried Scrooge. “No more. I don't wish to see it. Show me no more!” (48)

In every scene of Stave Two, in fact, the Ghost of Christmas Past shows Scrooge the extent to which he’s shrouded his essential nature—that of love—beneath a fear of poverty that consumes and controls him even as he maintains his outward pretense.

That underlying goodness is why Scrooge has hope of redemption. And it’s why what crowns Scrooge’s conversion at the end of Stave Four is not the fear of death so much as the realization that, if he were to continue on his present course, he would die alone, unmourned, and unloved (even Marley, we learn on the first page, had a sole friend and mourner in Scrooge). Scrooge finally understands that the most abhorrent poverty is not the poverty of wealth, but the poverty of love, and thus he obliterates the mask behind which he’s long hidden his authentic self.

Marley, on the other hand, must have been fundamentally selfish, because he was clearly given no such redemptive opportunity. Dickens leaves us guessing as to Marley’s backstory, but I suspect that Marley, who is likely older, repeatedly impressed his selfishness upon the younger Scrooge. By these acts Marley amplified Scrooge’s fear to the point of corrupting him sometime before calling off his engagement to Belle. I think, then, that Marley’s soul was pained with the "incessant torture of remorse” not only for his ruthless neglect of “the common welfare,” but also for his role in corrupting another to that same end. He thus sought atonement in the hereafter by pleading on Scrooge’s behalf with the powers above (the “other ministers” in the “other regions” mentioned on page 26). “He’s a good soul,” Marley might have said. “His evil is wholly my doing. Please, therefore, grace dear Ebenezer with a means of redemption.”

And thus does Scrooge receive that grace, which is again why I say that Scrooge’s core nature must be something other than how we usually think about him.4

Even more revealing, though, are the implications of the story’s title and how Dickens describes Scrooge at the end of the book, which, as noted earlier, are the subjects of Part 2.

Until then, share your thoughts, especially your own literary favorites and whether you did initially react to my choice of Scrooge!

(If you like this post, bless the Algorithm Angels, the Digital Devas, or whatever you’d like to call them by selecting the “heart” icon ❤️ even if you’re not a subscriber. It helps!)

And, lest you’re wondering, I have, in fact, taken a drink out of a toilet. Truly. It was a brand-new, never-used, and perfectly clean toilet that I was installing during a construction project. Once I’d cleaned the bowl and filled it for the first time, I leaned in and took a sip for the singular purpose of being able to drop a shock bomb into future conversations, like this one, with no shred of hyperbole or deceit!

This bias of in modern-day retellings is revealed especially in dialogue that’s given to Scrooge that isn’t present in the written story. From what I can tell (and perhaps one day I might do a thorough comparison), those additions usually reinforce the bad-Scrooge image and thereby heighten the drama of the climax, whereas in Dickens’ original Scrooge softens well before the scene in the graveyard.

Page numbers are from the Tole Classics printed edition of A Christmas Carol.

Another spiritual/metaphysical possibility, that would require an essay of its own, is that Marley has taken onto himself a load of Scrooge’s sin or karma, a tremendous sacrifice that’s possible only for beings of high spiritual advancement. Doing so would make Marley a saint in his own right.