Inspiring the transition from self-sacrificer to self-transcender in fiction, part 3

Spiritual practices that allow grace to flow

(If you like this post, selecting the ❤️ to bless the Algorithm Angels.)

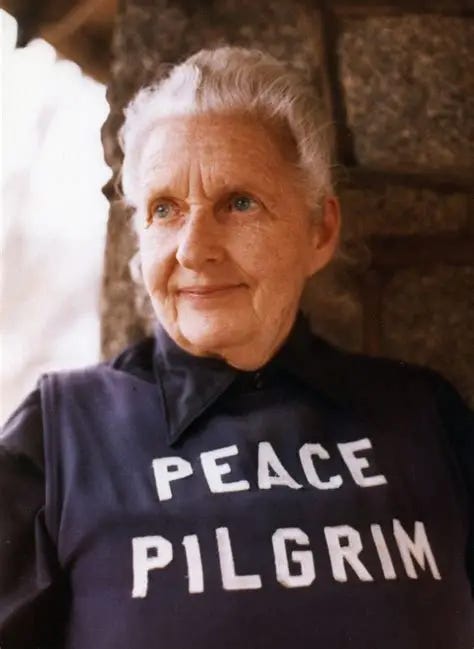

The first truly spiritual book that I read by choice was Peace Pilgrim: Her Life and Work in Her Own Words, which my wife’s high school guidance counselor had given her a few years earlier. Peace, as she’s called, was genuine, home-grown American mystic and, in my estimation, a saint, which to say, a real self-transcender. You can find the details of her life (1908-1981) and pilgrimage on peacepilgrim.org, but I think it’s best to just read her words.1 They certainly had a profound impact on me because I read that book precisely when my own spiritual search was really kicking into gear, compelling me upwards out of the self-server pattern and toward that of the self-transcender.2

Peace Pilgrim embodies the famous dictum attributed to Gandhi, “Be the change you wish to see in the world,” which is often quoted but, alas, seldom followed. Many well-intentioned people think that they have to change everything in their lives at once and quickly become discouraged when they struggle to modify even one part of their routine. What seems to happen next is that they turn their energies toward trying to change other people, which can unfortunately lead to anger, bitterness, and to exert power over others to force them to change.

What’s encouraging about Peace’s journey is that even as a saint-in-the-making it took her fifteen years to “be the change” she sought, thus setting an example not so much of the outcome but of the process. The first two chapters of Peace Pilgrim: Her Life and Work in Her Own Words document both how she first made a transition from the self-server attitudes with which she was raised into those of the self-sacrificer (pages 1-7), and then how she made the further transition (over those fifteen years) to the self-transcender pattern (pages 7-9).

Better still for our purposes here, she also articulated (pages 9-24) exactly those kinds of steps that I referred to at the end of Part 1 of this series: “deliberate steps to clear out personal opinions, attachments, and ideas about how things ought to be in order to become a better channel for God’s grace” (grace again being God’s light, love, joy, peace, wisdom, and power). These are the steps that lead a self-sacrificer on an upward, heroic arc.

Even more encouraging and apropos is that she gave those steps not as a rigid sequence but as a self-paced framework:

The steps toward inner peace are not taken in any certain order. The first step for one may be the past step for another. So just take whatever steps seem easiest for you, and as you take a few steps, it will become easier for you to take a few more. (9)

The very desire and willingness to engage in this process is, ultimately, what I think marks the first transition to the self-transcender pattern. To inspire a self-sacrificer upwards in fiction, then, means encouraging and cultivating that desire and willingness in some way. And a story doesn’t have to try to do everything all at once, either: it’s enough for any given story to work with just one of those steps, however small, and present it in a relatable and inviting manner. That’s exactly I sought to do in my short story, The Mystic Key.

By doing so, a story helps readers consider the change in question as a real possibility in their own lives, and perhaps also to become aware of victories they’ve already won but hadn’t recognized or valued.

If a piece of fiction accomplishes that, then it not only helps a reader find greater, lasting fulfillment but also helps to change the world. Gandhi knew what he was talking about.

Effects of different types of steps

What are those steps with which fiction can inspire readers to take in their real lives to make this transition? They’re really all those universal truths—and their association actions—that we find in every wisdom tradition, like the Ten Commandments. Jesus’ Beatitudes, the Bhagavad-Gita, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, and the Eightfold Path of Buddhism, to name a few.3 We find them also in the writings and sayings of many saints and spiritual teachers like Peace Pilgrim.

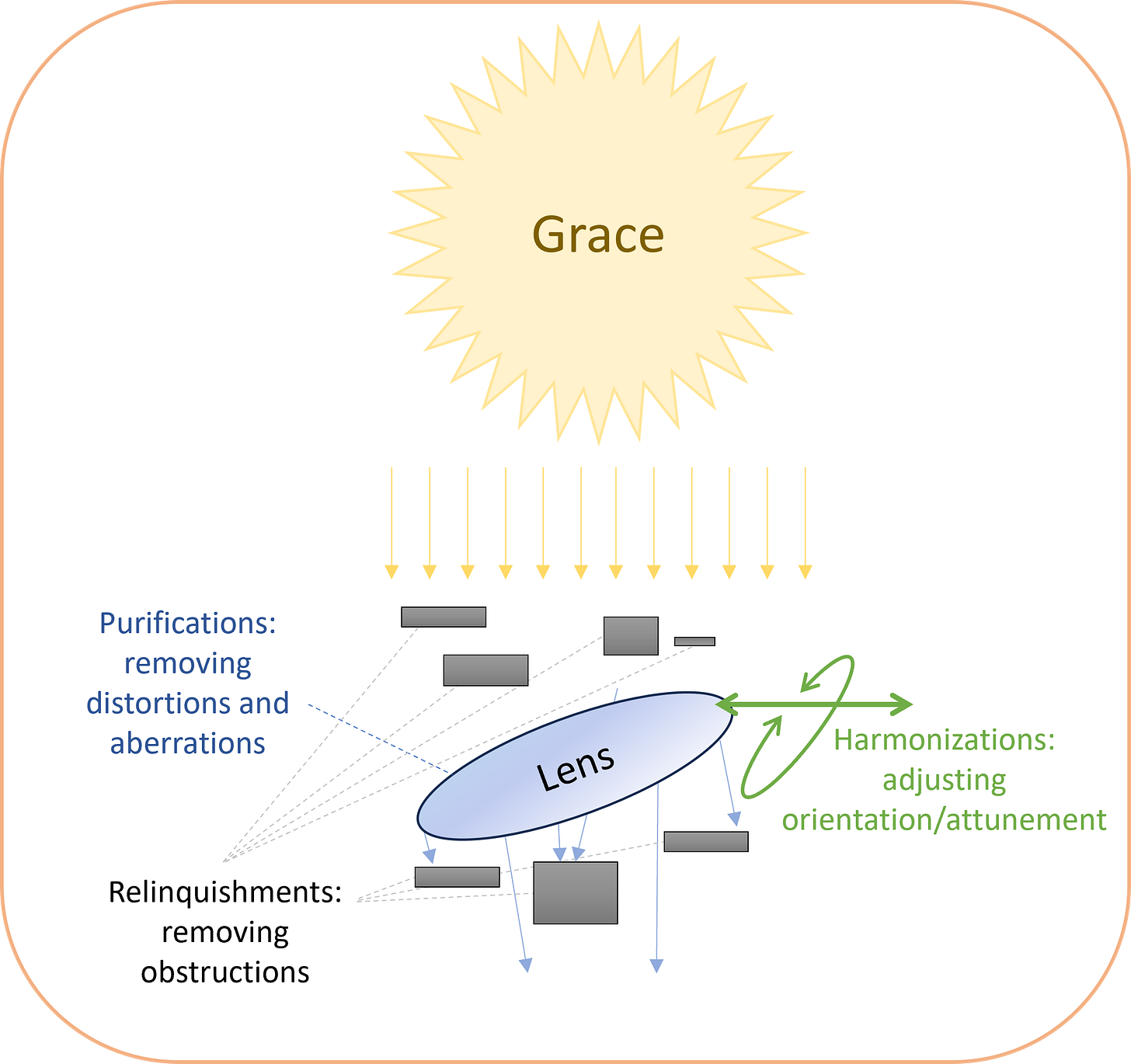

Peace Pilgrim, for her part, grouped various steps or practices into relinquishments, purifications, and preparations, the latter of which I think of as “harmonizations” given that the sequencing isn’t important. Here’s how we can relate them to the lens analogy from Part 1:

Relinquishments (don’t’s): letting go of those behaviors that obstruct or block the flow of God’s grace from reaching one’s lens and also obstruct whatever grace happens to make it through. These include Patanjali’s yamas and the “Thou shalt not’s” of the Ten Commandments.

Purifications (do’s): actions that clear distortions and aberrations from the lens. These include Patanjali’s niyamas, the observances of the Ten Commandments, Jesus’ Beatitudes like “Blessed are the peacemakers…,” etc.

Harmonization (devotion/concentration): actions that that essentially position and orient one’s lens to more fully receive God’s grace.

If I may indulge in a technical diagram, we might illustrate these as follows:

This visualization shows why the ordering of steps doesn’t matter: every effort to remove obstructions, improve the clarity or quality of the lens, and position/orient the lens for receptivity contributes to a greater flow of grace, no matter how small. “No sincere spiritual effort is ever wasted,” assures Krishna in the Bhagavad-Gita. (II:40)

The diagram also suggests that God’s grace is always present and available to everyone. “But as many as received him,” St. John writes, “to them gave he power to become the sons of God.” (John 1:12) And that is the secret of finding that lasting fulfillment that that everyone is ultimately seeking: once you clear away the obstructions and distortions and attune or harmonize yourself with the flow of grace, the ever-new Joy of God/Satchidananda is just there. It’s not something we have to achieve: it’s something we simply have to allow.

That process of allowing, though, still requires agency, the deliberate choice to act rather than be merely pushed along by circumstance or others’ actions. This is where fiction can inspire readers by depicting relatable characters who make choices and bear the consequences (good or bad). We’ve already talked about the tragic arc in Part 2, wherein a protagonist essentially takes opposite steps and shuts out the flow of joy. Tragic arc characters learn through suffering and indirectly encourage a reader to take positive steps by illustrating the results of the opposites.

In a heroic arc, on the other hand, a self-sacrificer protagonist faces and overcomes challenges when taking any of these steps, realizing that natural flow of joy that’s experienced by the self-transcender. Such stories directly encourage a reader to take similar steps.

Either way, a protagonist’s relationship to these possible steps depends on where they’re coming from and where they’re going along their arc, which leaves plenty of latitude for creative exploration.

Self-effort vs. grace and the role of going into silence

Before delving into specific steps within the different categories, which we’ll do in Part 4, we need to pause and clarify the contentious question of self-effort vs. grace. This is because all these steps constitute a body of “spiritual practices” that one undertakes willfully, which means that some self-effort is involved.

In Ephesians 2:8–9, St. Paul says, “By grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God: Not of works, lest any man should boast.” Many people are fond of quoting these lines to condemn deliberate spiritual practices or self-effort of any kind, essentially saying “Because grace does all the work, nothing we do actually matters.” And they’re right if we think that it’s possible to produce grace by self-effort alone—that’s the boastful part. But, as the earlier passage from St. John says quite clearly, receptivity is still vital. If the sun is shining on a window, we must choose with our own free will to open the shades to let in the light—the light won’t force those shades open on its own.

In fact, Paul’s very next statement in verse 10 (which isn’t often quoted with the others), states quite clearly that “good works” are the very reason for which we were made: “For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus unto good works, which God hath before ordained that we should walk in them.”

What, then, are “good works” if not all manners of uplifting or God-reminding activity, whether in service to others or to simply open oneself ever more fully to God’s grace? And what are Jesus’ Beatitudes but an exhortation to uplifting action and self-effort that helps one experience blessedness? “Blessed are the merciful: for they shall obtain mercy. Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God.” (Matthew 5:7–8) These verses imply meaningful action.

Sincere spiritual practices, then, are an integral part of the self-transcender pattern, as just about every saint has demonstrated. And the foundation of those practices is a regular withdrawal into inner silence—prayer, contemplative prayer, meditation, etc.—which, put simply, is time spent alone with God and with God alone. It’s where we set aside all those aspects related to the other behavioral patterns—sense engagements, personal ambitions, and even whatever work we might do for a noble cause—and to set aside, as best we can, the thwarting crosscurrents of ego to be completely receptive to reality. I think that’s what St. Paul meant when he said, “I die daily” (I Corinthians 15:31)—dying to outer engagements for a time, including any sense of duty, to assess the clarity and orientation of one’s lens and what obstructions there might still be to the flow of grace.4

Is engaging in spiritual practices a selfish and/or irresponsible thing?

Ironically, just as some religionists condemn spiritual practices as “works” of which one might boast, those same practices are often condemned by self-sacrificers, religious and secular alike, who are obsessed with political approaches. They claim, like the graphic below illustrates, that withdrawing into silence, working on oneself, and otherwise not spending all of one’s time engaged in activism is both selfish and irresponsible given all the suffering that exists in the world. “Silence,” they’ll say, “is the voice of complicity.”

Given what we discussed in Part 2, this attitude makes sense for politically-minded self-sacrificers or self-servers who seek power: those who withdraw more into themselves are no longer available as pawns in political power-games.

To those who are looking for outside-in (political) solutions, too, self-transcenders also appear to be “doing nothing.” But self-transcenders aren’t inactive: they’re simply looking for inside-out (spiritual) solutions instead.

Consider this: whence do all those “political” problems originate in the first place? They arise from conflicting desires. Most people want to remake the world according to their personal vision of a “good life,” whether it’s being comfortable and entertained, amassing power and wealth, or serving a cause (which often means imposing one’s vision upon others). That means they’re trying to push or pull the world in such a way as to benefit themselves at the expense of others, hence the conflicts and the attendant sufferings for on the losing side of the equation.

The lack of peace in the world arises largely from the lack of peace that human beings experience in themselves. The way to lasting peace and joy, then, is to stop pushing and pulling on the world. How do you do that? You relinquish desires and find greater peace and joy in yourself without requiring the world around you to change according to your whims. You let go, and by letting go you undermine the very source of conflict even as you discover lasting fulfillment in the flow of God’s grace and Satchidananda. And is that joy not more inspiring to others than shouting angry slogans and leveling accusations of complicity and complacency?

Far from being selfish and irresponsible, then, spiritual practices must be counted as some of the most rebellious and seditious acts within a world otherwise dominated by selfishness and self-involvement.

Indeed, they are not for timid, vague, or otherwise weak natures seeking an escape from reality, but are essential for all who wants to develop their full potential as a human being.

We’ll take a closer look at specific possibilities in Part 4.

The secret of bringing peace on earth is to remember that whatever peace you bring must begin on that little piece of earth where you live. —J. Donald Walters, from Secrets of Bringing Peace on Earth

(If you like this post, selecting the ❤️ to bless the Algorithm Angels.)

Visit peacepilgrim.org/free-offerings to obtain free copies of this (and other books) in print, PDF, or audiobook.

This was in early 1993 when I was riding the wave of a superconscious experience that inspired my writing Inside OLE 2, which I relate in Chapter 10 of Mystic Microsoft. During that same period I also read three other books that had a great influence on me: Marsha Sinetar’s Do What You Love, the Money Will Follow and Ordinary People as Monks and Mystics, and The Zen of Seeing by Frederick Frank.

The Qur’an also contains many behavioral guidelines, though not in a consolidated list. But books like The Islamic Ethics and Behaviors offer compilations, as other authors also do for the Bible and other scriptures.

That’s something I sought to depict in Wondrous Chapter 1.